Strangers in a strange land part 2.

The idiosyncratic crazy individualism of Foujita Tsuguharu.

The Japanese encourage a self-propagated myth that they are a people who are governed by a type conformity that totally suppresses individuality.

This is the face they wish to present to the world. It is complete rubbish.

There is a richness in Japanese anti-conformity which exists as a thread that can be teased out, if you have the patience and the curiosity to look for it.

In all the reading and the conversations I have had regarding Japanese martial arts, the one thing that sticks in my mind is the spirit of innovation. Without it, the higher Japanese arts would have stagnated and crumbled into dust.

To examine this, it’s time to look in another time, another place and another discipline.

Historical context.

Setting the scene; the infamous Jazz Age of Paris in the 1920’s, the world of Gertrude Stein, Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, Picasso, Guillaume Apollinaire and… painter ‘Leonard’ Tsuguharu Foujita (to give him his westernised name).

Although not a martial artist, Foujita was an artist nevertheless. Someone who brought his Japanese-ness to the west in search of an ideal and a dream. He never abandoned the essence of his national identity; he carved something new out of it and created an uncompromising blend in the work he produced and how he presented himself as an ‘artwork’.

To explain.

At the height of his fame in 1920’s Paris, Foujita would strut around Montparnasse and frequent the cafes, dressed like a dandy, with his distinct ‘bowl-cut’ hair style, and equally characteristic round horn-rimmed glasses; sporting a discrete gold earring. Foujita was fluent in French and socially confident, particularly with the ladies (he was married five times but was not averse to same-sex relationships). He would consort with Picasso and flirt with Josephine Baker.

The Parisian BoHo set called him, ‘Fou Fou’ and he once turned up to the opera with a lampshade on his head, telling everyone it was Japanese national costume.1

1924 photo of Foujita. Credit: https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/foujita-cats/

But first; the back story.

Fujita Tsuguharu (1886 – 1968). Born in Tokyo, son of an army officer and medical director. Foujita (note, western spelling) was specifically interested in the visual arts from an early age and took the traditional route through art education, but was drawn towards things European (he had studied French at High School).

Instrumental in developing his ideas was his exposure to Kuroda Seiki, an influential artist and internationalist (Kuroda’s story is also really interesting). This resulted in Foujita setting off for Paris at the age of twenty-seven in 1913.

Paris.

While in Paris, although he had some Japanese contacts in the art community, somehow, his outgoing nature and urge to throw himself fully into the bohemian lifestyle and really converse with the creatives, launched him on a path which was idiosyncratic and very different to the other Japanese artists hanging about on the fringe.

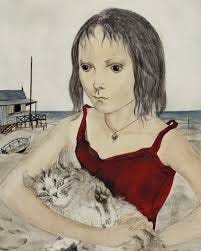

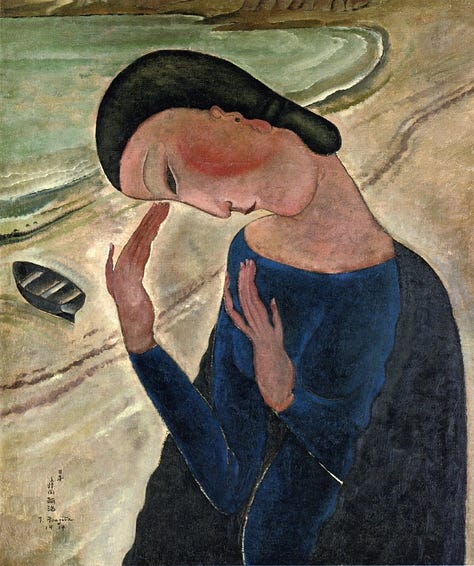

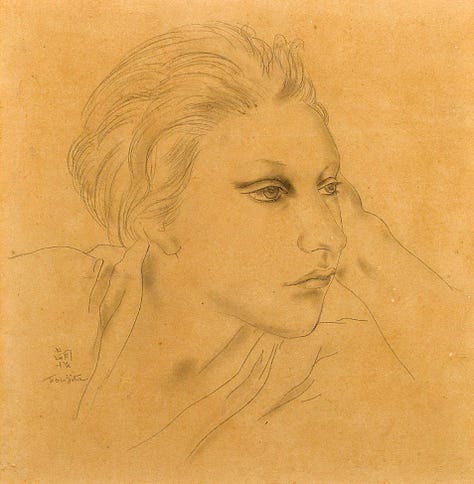

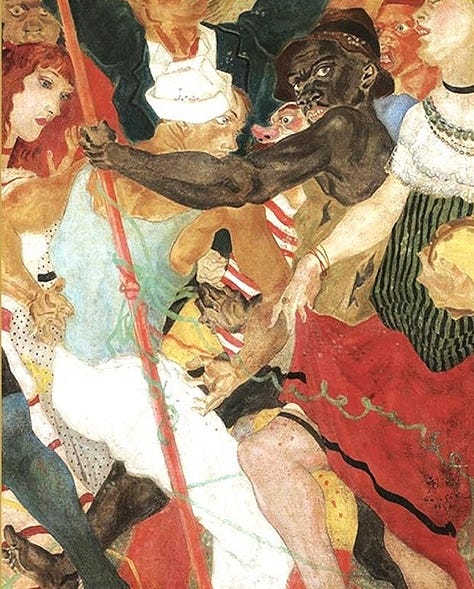

Selective gallery of Foujita’s works.

I cannot understand for the life of me why Foujita’s name is not talked about more. As an artist, he was not a copyist or a wannabe, neither was he content to produce pastiches of what was currently in vogue. He was very much his own man and acted like a sponge to the influences of those around him, like Picasso, Braque, and Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.

Foujita was in the right place at the right time.

Foujita in studio 1923. Source: Public Domain.

By good fortune he moved into the Bateau-Lavoir a rundown rathole of a building, more like a semi-ghetto, semi-squat for all the creatives. Anybody who was anybody was operating and living in the twenty ‘studios’ including Picasso and Modigliani.

Paris in the jazz age; is that Foujita in the background, 4th from the left? Certainly looks like it.

Muses and romantic partners.

Foujita first married in 1911, to a Japanese girl who, for various reasons, never moved to Europe with her new husband. She seemed quite content for him to pitch his all into a new life as an artist in Paris.

The marriage was officially ended in 1916 when Foujita moved temporarily to London. It was also at this point that he realised that he no longer had to rely on money from his father. This was a risky decision because Europe at the time was in the grip of WW1 (Foujita actually worked for the Red Cross in France at that time).

Foujita and the famous Parisian muse Kiki of Montparnasse. Picture credit: Photographer, Iwata Nakayama 1926.

After the end of his marriage, he didn’t hang about. Once back in Paris he met and hastily married Fernande Barrey, who had been a model for the artist Modigliani. Now that the roaring 20’s had erupted, it was Fernande who had the contacts that enabled Foujita to become an established artist – the dealers at the time became very interested in him.

In 1922 he was introduced to Lucie Badoul, who became one of his models. In 1924 he divorced Fernande and Lucie became his new muse and partner.

By about 1925 Foujita was having serious problems with the tax man and went off on his travels to turn his back on his woes. (He wasn’t able escape bankruptcy though).

After trying to establish a toe-hold in the United States he returned to Paris to face the music. Lucie had now shacked up with someone else and Foujita then became involved with a former dancer called Madeleine Lequeux (aka, Maddy Dormans).

Foujita and Madeleine decided that maybe South America was a good idea, this was now 1931/32. He had some success exhibiting in Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Peru and then Cuba.

Japan 1933 to 1949.

Foujita and Maddy weren’t to know that a return to Japan at this time was liable to be troublesome. Foujita, the misfit couldn’t escape the taint of the west (this is something I have heard from modern Japanese who sometimes find it difficult to fit back in to Japanese society after a period of living in the west. They are somehow seen as being not quite Japanese anymore).

Maddy only lasted until 1935, when it all became a bit too much for her. She returned to France without her husband and died a year later.

Foujita didn’t waste much time and married his 5th wife, Horiuchi Kimiyo.

War artist.

Foujita had his one single skillset, his painting, and very quickly he was involved as a Japanese war artist. He struggled to get acknowledged in Japan. The critics found it difficult to stomach the French style of painting (as they saw it). After the war it all rebounded on him. By a whisker he escaped being condemned as a war criminal (promoting fascist propaganda etc.) and in the west his reputation was tarnished.

And return to the west he did.

Aftermath and final years.

In 1949 Foujita and Kimiyo manged to get a visa to the USA. Luckily, with sponsorship, he landed a teaching position at the Boston Museum Art School, but his painting and exhibition plans met with resistance and protest. This was an unhappy time for him and it wasn’t long before Foujita and Kimiyo moved back to France.

For the rest of his days he was a kind of jobbing artist; some book illustration, even a little costume design, but his paintings were seen as twenty years too late.

The couple renounced their Japanese citizenship in 1955 and became Catholic (this was when Foujita adopted the name ‘Leonard’).

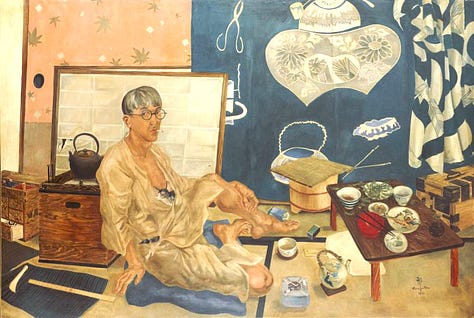

Leonard Foujita later in life.

After his death in 1968 in Switzerland, there were attempts to restore his reputation through retrospective exhibitions in France, America and even Japan, but they never quite gave him the credit he deserved. I am hopeful that, rather late in the day, the light of Foujita will be given chance to shine.

Conclusion.

Although not a martial artist, Foujita’s example reveals something of the Japanese character that bubbles beneath the surface. Like a carbonated drink shaken with the cap firmly on, something is gonna pop. With the lid screwed down and given enough of the right ingredients (and fermentation) the cocktail has the potential to be an explosive creative mix.

To continue the metaphor; the ‘yeast’ element for Foujita was his exposure to western art – ironically, very similar to how Van Gogh was hugely inspired by Japanese art; the creative traffic travelled in both directions.

I do hope my regular readers will forgive this slight diversion away from martial arts, but I always said that Japanese culture was not straightforward and deserves the wider lens approach.

Gallery image credits: Stephen Ongpin Gallery. Arthive.com.

In the early 20th century the French had a liking for names with repeated sounds; like, Coco, Lulu and Fifi. Fou Fou was always going to fly.

Like the cut of his ghib