A comparison of examples of ‘martial arts’ that were handed down through the generations, and how they survived, or didn’t.

In this part:

· Domenico Angelo – European fencing tradition.

· In part 2: Yang family Tai Chi.

The three-generation rule, as applied to family fortunes.

There is a theory that, in general, wealth in families only lasts for three generations.

The basic model is that the first generation is the entrepreneur, an individual who makes bold and ambitious moves to establish a reputation, connections, unafraid to go out on a limb, and thus accumulates wealth and status. Quite often, uprooting to another part of the world.

The generations that follow could be threatened by several factors:

· Inheritance passed through too many offspring, which dilutes the assets.

· The inability to weather life’s calamities.

· Internal strife, divorce, fallings out, etc.

· Bad business decisions.

· Poor management; inability to bring people onside, or handle external threats.

· Being blindsided and unable to judge the trends and change with the times.

But you can also include a more poisonous factor; changes in values, mixed in with complacency by just taking things for granted. If you like; a feeling of entitlement, that your pedigree means that the world owes you a living.1

If martial arts skills are family assets (alongside other assets) I think it would be interesting match the above criteria to dynasties of martial artists through a small selection of examples.

Case 1: The Angelo School of Fencing – England 18th and 19th centuries.

Domenico Angelo (1716 – 1802) was an Italian-born master of fencing who, through some clever and opportune patronage ended up in London in 1750, initially after an affair with a well-known English actress. But he caught the eye of the very highest in London society, including The Duke of Pembroke and the dowager Princess of Wales. Here was the progenitor, the entrepreneurial start of the line.

Angelo Domenico Malevolti Tremamondo; to give him his full name.

Just what was it that defined Maestro Angelo’s unique qualities?

· Amazing courage; in first setting up a business in the heart of a new city (in Soho Square), but also the guts to be able to take on challengers in duels, building up a solid reputation.

· Connections; not necessarily through his own countrymen, (his merchant father actually cut him off when he found out that his son was earning his living through the sword) leading to patronage, and therefore financial backing.

· An excellent pedigree as a skilled swordsman. Firstly, through the Italian method of fencing, but then in Paris, studying under the famous Bertrand Teillagory.

There was an urgency among the English aristocracy for the training of their youth in the art of the sword. This was based upon the perceived risks of all these young bucks running around Europe, getting drunk and doing ‘The Grand Tour’, fresh meat to any ambitious thief, highwayman or footpad. In a nutshell; the skills were in demand.

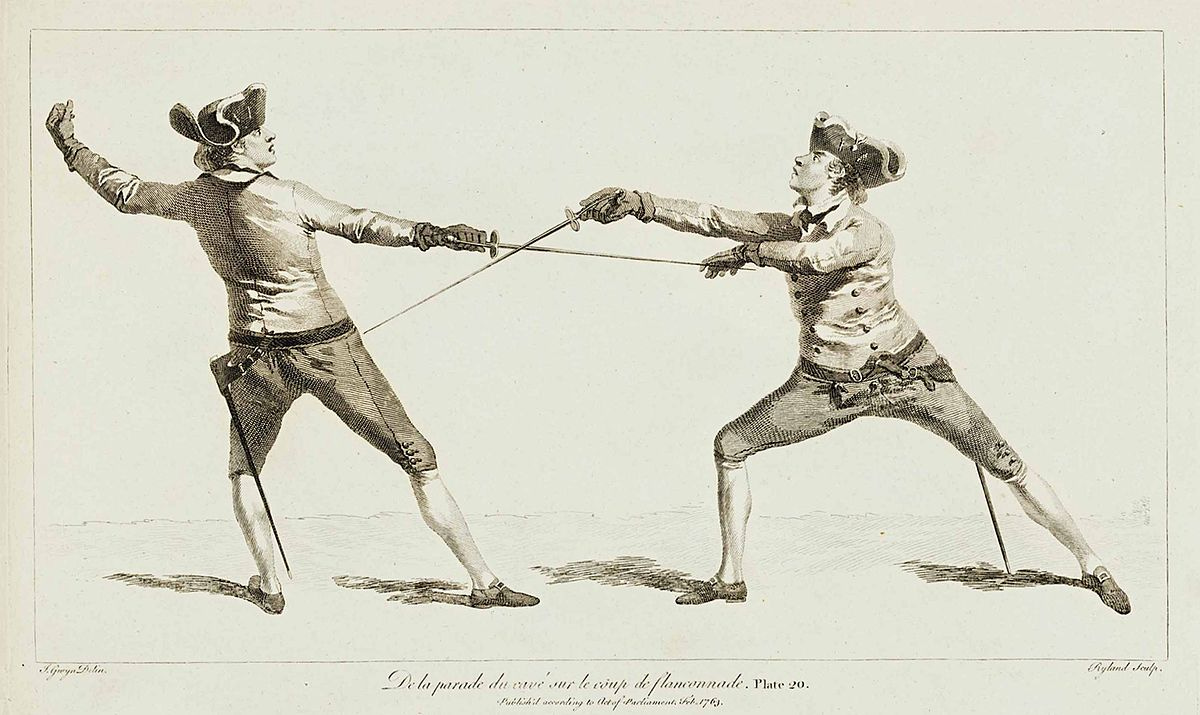

His significant contribution was the publication an elite folio/book published through the backing of over 300 well-connected aristos. This was to become the Angelo family bible for the next generations; which, as we shall see was not necessarily a good thing.

Angelo’s folio.

Domenico was the launchpad for the following lineage of Angelo’s to follow on, and they did; but in their own way.

Second generation; Harry Angelo (1756 – 1835).

By W. Bond, after painting by W. Childe - Angelo, Henry. (1828) Reminiscences of Henry Angelo. Frontispiece, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=82665165

Not at all like his father, but ambitious in his own distinct manner.

Technically, he learned his skills with another master in Paris before moving into the family business. Relations between father and son were strained and Angelo Snr. was resigned to backing away from the business into his own little niche, teaching sword at Eton College.

Harry’s business pattern.

What Harry did was interesting in two respects:

Firstly, he democratised his clientele, as in, he wasn’t so picky that his students weren’t aristocratic. A similar thing happened with the Japanese martial arts teachers after the samurai were disbanded – begrudgingly they had to teach commoners the arts that were previously for the warrior elite. But the samurai were pushed into it; it was either commodify the one skill you had, or slip into penury and starve. I am not so sure Harry was under the same kind of pressure.

Secondly, he turned his teaching establishment into a kind of salon, where they trained hard and partied harder. Harry Angelo’s clique celebrated their various wins with copious amounts of booze and then Harry, being a bit of Bon Viveur and self-proclaimed chef, would cook for his entourage and their various hangers-on. This actually added to the popularity and culture in the Angelo school; something his father would never have suffered. Harry Angelo was indeed a smart businessman.

Harry Angelo’s salon, by Rowlandson.

Diversification is always a good way to boost your business.

Technically, Harry was not really a progressive in the field of fencing; although he always had an eye for a fresh opening, and was quick to take up the commission of developing a method for the military sabre; much needed by the British army in the later 1700’s. Harry also picked up a similar contract with the navy, to develop a cutlass fighting method. The Angelo’s passed this commission down to the next generation, so in all, a good move.

The next generations seemed competent inheritors but were unable to move with the times. As a telling example, Harry actually had to give way to allow boxing to be taught in his establishment, but failed to read the writing on the wall. It has to be remembered that Lord Byron’s interest in the pugilistic arts made boxing fashionable at that time.

The flaws and the decline in the Angelo inheritance.

I mentioned earlier that Harry Angelo’s reluctance to technically move with the times was one of the weaknesses of the Angelo tradition.

It is odd that Harry learned the progressive stuff in Paris in his early years and then fell back onto what was taught in his father’s book. There are probably a couple of reasons for this, one being that promoting the various editions of the book brought money into the business and the other being just trading off his father’s name. I suspect that the latter reason may also be a millstone round the neck of other martial traditions – in that their kudos is partly derived from an iconic ancestor.

Next generation; Henry Charles Angelo (1806 - 1866).

More sober and measured than his father. But by this time fencing as a duelling system had been long overtaken by the pistol, and if it was exercise and a good manly sweat you wanted, then boxing was all the rage.

The Angelo’s managed another generation after Henry Charles, who may also have been called Henry, making him 4th generation. He had sons, but none of them wanted to be involved in the family business so it just faded away, and is now a footnote in British sporting history.

Angelo’s conclusion.

The Angelo’s just about managed four generations, but they were really finished by the third in the line. The train had left the station and they were abandoned standing on the platform.

In England and Europe, the fencing tradition never truly died, as is evidenced by fencing as an Olympic sport, though it’s hardly a blue-collar activity. (As a long-time school teacher, the only place I ever saw it in educational environments was at the elite Harrow School).

The second generation was beset with inter-generational frictions. Angelo II might have been a good business manager at the time and figured out the importance of solid upper-crust connections, but I don’t get the impression he was trying to build up a legacy through technical fencing.

The Angelo story has so many markers within the general pattern of the ‘three generation’ rule. It would be really interesting to go further into the Angelo family’s internal dynamics, but the information would take a much more skilled researcher than myself.

Note: For info on the Angelo family, I am indebted to J. D. Aylward’s book, ‘The English Master of Arms’.

This point is one of the most compelling arguments against the idea of a meritocracy. If everyone inherits their parent’s/grandparent’s wealth, wouldn’t the social tree become oh-so-very crowded in the upper-most branches? I recommend Michael J. Sandel’s book, ‘The Tyranny of Merit’. I was a confirmed believer in the meritocracy, until I read Sandel’s book.