A basic rule of Wado - Do not use more energy than you need to do the job.

A dip into one of the core concepts of Wado karate.

I want to try to avoid befuddling this theme by adding Japanese terminology to it, (but believe me, it is there) and instead try and keep it grounded in practicalities and easy to understand frames of reference.

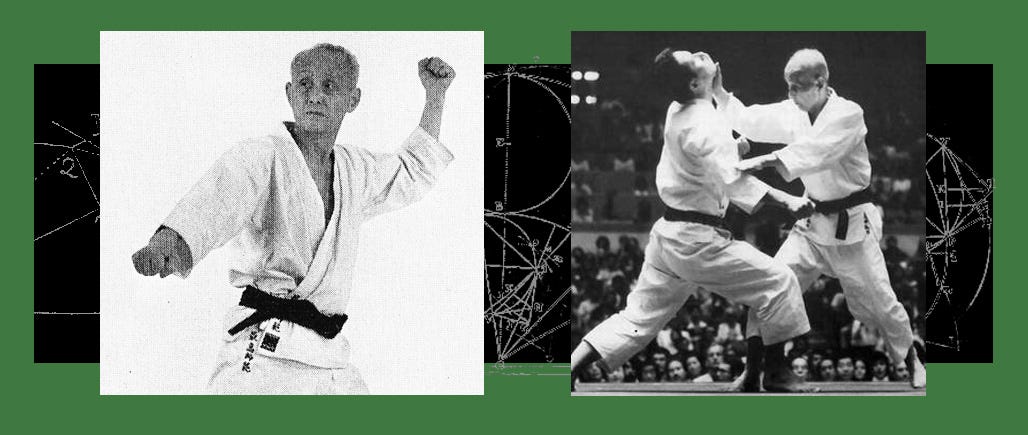

Master Otsuka’s rules.

I have said in the past that the founder of Wado karate, Otsuka Hironori (1892 – 1982) left behind some pretty clear guidance as to what are the identifiable qualities of his system. I think he planted these seeds in the full knowledge and intention that Wado was an evolving system that was supposed to stretch on into the future beyond his lifespan. This, in itself, is entirely consistent with the concept of Shu Ha Ri as understood in Japanese Budo.1

Otsuka Sensei had several layers of core principles; some were admonitions, others were manifested through actual physical lessons. Rules were laid out, examples were presented; it was all there, but it was open to individual interpretation – and this was probably where the only available weakness resided. Take any one of those admonitions/rules/rubrics and it is possible to totally bend it out of shape, (or claim your own individual ‘interpretation’) and then the whole project falls apart.

Examining one of the rules in isolation.

I want to look at just one of those concepts, which really is a rebuke, a warning, and it is this; ‘Do not use too much power/energy (to achieve your aim)’. At one level, this is a typical Otsuka call for economy, but it’s more than that.

For me, this is one of the most important concepts, and also one of the most abused, but not deliberately, more unintentionally. It’s a victim of our urge to max-out on our energy application, almost as a sense of duty as to what we think we should be doing to achieve our aim; well-intentioned but inevitably misguided.

I have to ask this question: At any point, in any fighting system, has anyone ever been told to dial-down their application of power? Very unlikely… the quest tends to be for more power! But, maybe it’s about definitions. Maybe we are looking for a more powerful effect?

What if the objective was for more efficiency, or greater effectiveness? Perhaps we can imagine a situation whereby we can achieve a decisive, conflict-resolving outcome and then later congratulate ourselves that we used the minimal of exertion? Wouldn’t that be more desirable?

What is the problem, and what would be ideal?

What I am talking about here are two things; ways of moving that make the body more efficient, and the flip side; ways of moving that make the body less efficient.

Starting with the things that get in the way:

· One of the biggest problems is too much tension – often where one muscle group actually inhibits the job of another muscle group; a bit like driving with your foot on the brake and the accelerator at the same time.

· Focussing too much on one body part, or one part of a move, when performing any action, like a strike or a kick (how often do you see people cramping up their upper body while performing a kick, effectively locking themselves up solid and inhibiting their ability to flow with the action?).

· An habitual reliance on an idea of what strength is that is based upon a false premise/reality. Guys are particularly prone to this; for them, a fighter is supposed to be ‘strong’… yes, but how should that strength manifest itself?

· Tension that appears as an embodiment of an overcooked drive towards ‘Intent’ (my own Sensei has been known to criticise people who have, “too much Intent”, they go after their opponent like a dog chasing a ball, which in fighting makes them oh so predictable).

What are the qualities that would enhance efficiency, looking at it from a Wado perspective?

· I would start with the appropriate deployment of energy; only use enough to do the job and use it smart! I was once working with another Dan grade on the second move of Kihon Gumite Ipponme; he was insistent on emphasising the power of the final left-hand strike, in fact he was totally sold on the idea that it was entirely a power hit and nothing else. For me this was a static understanding of what was going on, there was no hint of the dynamic interplay. I know some styles believe in a policy of deliberate overkill; knock them down and then hit them eight times for good measure, but it’s not the Wado way. In Kihon Gumite, the opponent supplies the energy for you to work with and you engineer how you manipulate it with the smooth and efficient deployment of your energy – no need for overkill, the job has been done.

· Being careful where and when you commit your energy. Holding on to tension is a potential killer. I have seen people become stuck at a particular point, often a block, and then be unable to smoothly follow on to the next logical move. If it’s a power hit that you are trying to create, be sure you’ve got enough in reserve to swerve it if things don’t go perfectly to plan.

‘Ri’ and ‘Mu-ri’.

I said I was going to avoid Japanese terminology but I couldn’t resist this one as it fits so well.

Judo veteran and long-time Japanophile Trevor Leggett wrote about this in his book ‘Zen and the Ways’.

‘Ri’ is like the natural, uncorrupted universal flow, pure Principle, refined and unarguable logic and truth, the base and origin of all nature. A perfect spontaneous technique should resonate beautifully and harmonically with ‘Ri’, it is exquisitely balanced, without artifice or calculation and originates from nowhere, it just… is. At one level it is an ideal, and for the martial artist, an aspiration, a guide for the refining process. (This is the same ‘Ri’ as in the Wado adage, “Wa Suru Ten Chi Jin no Ri Do”).

‘Mu-ri’ is something done against ‘Ri’, i.e. something done badly, that rubs against the grain, has got to be forced to fit, it’s clumsy, ungainly, even brutal. Leggett describes it as ‘to force a result’, like shouting someone down in an argument.

Where does this appear in Wado?

If you look hard enough in your training you will inevitably encounter ‘Mu-ri’ more often than ‘Ri’. It might be something you observe in your own technique, where you know that you muffed it then had to force it to work, or you just failed to get a grip on the situation. But you will also see it in other people. Inevitably, when students are just beginning to learn they will encounter this all of the time, but they persevere and techniques become more expert and refined over time.

However, given that this one principle of ‘don’t use too much power to deliver your technique’ is so important to Wado, why does it seem to be the one that is either misunderstood or just ignored? Well, at least that’s my observation; I have seen it first hand and it’s certainly all over YouTube.

How to explain it?

For a while now I have been trying to think of an accurate analogy. The best I have come up with comes from my driving instructor from many years ago. When I was learning, he watched me changing gears and how I handled the gear stick. I was making it work but was fumbling it too often, which then mucked up my clutch control. The instructor decided to show me a more efficient way of changing gear which was smooth and virtually energy and error-free, many of you will know this technique called ‘palming’; the palm is turned and pressure applied sensitively to the required direction; resistance is minimal, making gear and clutch coordination effortless. What I was doing was slamming my hand on top of the gear stick and trying to jam it into what I thought was the right position – forceful, but really hit and miss and not a pleasant experience for any passenger.

In pairs work.

Unfortunately, I have experienced the Kihon Gumite version of my clumsy gear stick handling, and I have also encountered the opposite (the equivalent of the ‘palming’ method).

At the highest level of efficiency and expertise; I was once acting as Uke for one of the Japanese Sensei in Kihon Gumite; I put in my best shots (as was my duty) and basically seemed to fall into the worst of positions for me with the minimum of effort from him; I was just ‘done for’, I almost wanted to applaud!

Contrary to that, I have sour memories of having to suffer clunky, power-locked partner work at the hands of an Uke who I thought would have known better – and this has happened more than once; not only ‘Mu-ri’ but also a blatant contradiction to Otsuka Sensei’s tenet, ‘Don’t use more strength than you need to do the job’.

In solo kata.

The performance of solo kata is where karateka are most exposed to critique. I draw a distinction between the ‘training’ of kata and the ‘performance’. When you are training you are refining your kata in a mindful way; you are trying your best to improve, so you practice and then review and then practice again, restructuring and polishing and trying to encourage those ‘ah-ha’ lightbulb moments and also establish good habits to hardwire them into your system.

Performance is where you may be inclined to feel almost naked before your audience, and the intensity of this experience can be magnified depending on the audience – performing in front of a grading panel or competition judges can sometimes make people go weak at the knees.

These pressures are more inclined to allow bad practice to surface and particularly the inappropriate use of power or forced strength.

Experienced and long-standing Dan grades hopefully have a more mature approach to their use of energy and power. Although, it is not a given that this comes without effort and thought, it has to be deliberately nurtured and reviewed; you can’t assume that your body has just ‘got it’ with no effort on your part. It’s there if you look for it. Over time I have seen very senior Wado karateka who have deliberately taken the hard edges from their kata, without losing the authority in their technique; they generate energy but it is really difficult to see where it comes from.

In conclusion I would encourage all Wado karateka to ask some hard and searching questions; to look at how they define power, when is it over-done or wasteful? Just because something has more ‘thump’ doesn’t make it better. After all, Wado is not a blunt instrument; it’s more ‘surgeon’ than ‘blacksmith’.

‘Shu Ha Ri’. Put simply; it’s a three-stage evolution, you follow a tradition to the letter, you then evolve and develop and deviate, and finally you ‘break’ the mould, but ironically reinvent the core system on a higher advanced plane. I am convinced that Shu Ha Ri has both a micro and a macro element – but maybe that is for another blog post?

Food for thouht.....

Another stimulating point of view Tim. Personally, I also think that the study of the polarity between 'relaxation' and 'tension' is one of the most important elements of budo, and that the evolved Wado style offers important perspectives on this. Whether you approach that from a Western point of view and call it 'body mechanics', or from a more Eastern point of view and call it 'internal training', both approaches are ok. Indeed, what matters is efficient management of body energy and the employment of natural laws for maximum effect and minimum energy expenditure; that is, how one deals with incoming forces on the body: does one divert them or absorb them by developing purely reactive counterforce? Of the latter strategy, Okinawa-te is a very good example. And when one realises that virtually all Japanese karate styles are indebted to this, it is to Hironori Otsuka's great credit that he dared to think "out of the box" against all the orthodoxy of the time. And thus made Wado a maverick that brought it up to the level of, say, the sophisticated principles of Judo or Aikido.