Explainer: why this pic at the top of the post? Your challenge; identify the real Itosu from amongst this mixed bag of red herrings.

To set the scene.

Iconic movie moment; at the end of Stanley Kubrick’s movie ‘Spartacus’; if you’ve seen it you’ll remember it, “I will spare you all if you identify the body or the living person of the slave called Spartacus”, then, one by one the cry goes up, as they all say, “I’m Spartacus”.

The rush to identify the single elusive photograph of the Okinawan karate master called Itosu Anko has been cluttered with candidates from dusty Okinawan historical archives – ‘Surely, this man is master Itosu?’, then this man… Will there be no end to it?

I get it; to historians and archivists, they want to believe that it has to be out there somewhere.

In case you wonder who I am talking about. Itosu Anko (1831 – 1915) was the primogenitor of karate in the modern age. Although everything about him happened in the islands of Okinawa, his influence since his death has spread around the globe.

The Japanese junk shop.

When I was in Japan, I discovered in the city of Kyoto the most amazing junk shop. I didn’t realise that the Japanese did junk cum antique emporiums like we do in the west; maybe this place was a rarity; perhaps I even imagined it?

The shop was cluttered with all kinds of oddities, stuff that I couldn’t recognise or imagine how they put it to use; cooking utensils, ancient winter kimonos, so ragged that you would have thought someone had died in them, and crucially, for my narrative, boxes and boxes of 19th and early 20th century daguerreotypes and carte-de-visite; formal photographic portraits of single dignified Japanese individuals, male and female, unsmiling in their best kimono. No names, no identifications just shadows from the past. Maybe one of the photos was Itosu Anko, caught on camera on an unscheduled, unrecorded visit north? Fantasy – I know.

Lost faces.

I have seen similar things in antique shops and boot sales in the UK, ghostly anonymous proud individuals, somebody’s ancestor, great aunt, etc, but totally impossible to put a name to them, unless some family member has thoughtfully scribbled the important details on the back in pencil (which we all forget to do). They are individual visual haiku, odes to our impermanent lives.

Other examples.

The Americans are besotted with their own history. Well, you have to be if you’ve got so little of it. For a start; anything back beyond the Pilgrim Fathers is almost taboo, like it didn’t happen. But, for the Americans, the 1870’s is like way, way, way back; while for Europeans, the 1870’s is…yesterday.

Look at the case of the hunt for any photograph of the gunslinger known as Billy the Kid (1859 – 1881). Officially, really there is only one pic of Billy; not a particularly heroic one, just a youngster in ill-fitting clothes and a cheap hat leaning on a rifle. A gap-toothed goon who in modern times would be wearing a baseball cap and a hoodie and trying to steal your car while selling weed on street corners; that’s Billy.

There’s supposed to be another photo of him, standing outside a ranch with a group of desperadoes, not armed to the teeth and snarling into the lens, but instead playing croquet… yes, croquet, a demure genteel game with hoops and a wooden mallet; more cucumber sandwiches and tea than whiskey and beef jerky.

Billy, leaning on his mallet.

The croquet photo was discovered when its owner bought it for $2 in a California junk store in 2010; it’s expected to now have a worth of nearer two million dollars.

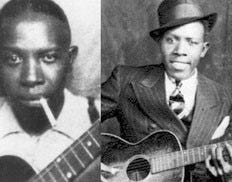

Same with famous bluesman Robert Johnson (1911 – 1938), only two photographs exist of him, with a desperate obsessive hunt to find any more.

Photography in Japan.

Note the years of the above-mentioned examples, including Itosu Anko, and bear in mind the meteoric popularity of photography since its invention in Europe in 1826. Itosu wasn’t born until 1831 and died in 1915. So, with that later date, enough time for it to be feasible for a photo to exist.

To put it into historic perspective; as far as photographic technology went, it took until 1848 for the camera to reach the backwater that Japan was considered at the time, and the Okinawa of Itosu was a backwater of a backwater. However, in Okinawa, it picked up pace really quickly, particularly for formal portraits and group pictures associated with institutions, like schools and colleges.

To be realistic; another factor that makes the search for the definitive photo of Itosu so challenging, is that during the Pacific War Okinawa was ravaged and burnt by advancing troops and so much was destroyed including documents and photographs.

The iconic master Itosu.

Why is he so important? The vast majority of all karate seen today flows from Itosu Anko. He was an innovator and a moderniser and, to some, is credited with the invention of the Pinan kata. He was the direct teacher to Funakoshi Gichin who took karate to mainland Japan.

The answer to the puzzle.

The numbered photos on the header image at the top of this post are made up of red herrings, or early assumptions, selected almost at random, and two particular images both eagerly identified by historians as master Itosu.

The first one pounced upon by karate enthusiasts happened in the early 2000’s, but has now been debunked and actually identified as a kendo teacher, Miyake Sango. This is number 4 featured above.

The second one, which some believe is more likely (right time, right place) is the blurry dignified old guy standing almost on his own in a school photo. This is number 2.

Interestingly, martial arts researcher, Dejan Djurdjevic has made another assumption, about one of the earliest formal karate photographs of Funakoshi Sensei (1921). In this group pic there are two vignettes in the top corners; unidentified; he thinks the one on the left is Itosu.

My suspicion is that these are probably photos of Okinawan dignitaries or minor politicians, or even the crown prince himself, as it was to commemorate his visit, though neither of them looks like the bookish Hirohito from pictures from 1921.

In conclusion.

I find myself impressed by the optimism of the researcher; but also the fact that photographic portraiture holds such allure. It’s as if the photographer has actually managed to capture the very soul of the sitter; the impossible achieved, with time frozen and compressed into a two-dimensional chemical process.

Portrait painting seldom works like that for me, with only a few very important exceptions – Hans Holbein and John Singer Sargent (look them up, you will be amazed).

Itosu will remain ever elusive, along with his long-dead teacher, Matsumura Sokon, who died in 1899. But, wouldn’t it be weird (and ironic) if a picture of him turned up first?