Westerners who have an interest in art and the aesthetic seem to have really picked up on this in the last twenty years. Even if that’s not your zone, it’s worth looking at from a cross-cultural perspective.

Definition: ‘Wabi Sabi’, “Japanese philosophy that embraces beauty in imperfection, impermanence, and the transient nature of existence”.

Broken down; ‘Wabi’ is a kind of subdued, austere beauty. While ‘Sabi’ equals the appreciation of ‘rustic patina’.

Put these two together and you have a meditation on objects and phenomena that contain a type of understated, much loved and even over-used utility. A cracked teacup, no material value in itself, but perhaps it is an adored family heirloom and has some sentimentality, even charm. This can include the simplest of objects, clothing or utensils. It might be something used and worn by being passed through many hands. These are objects that have a rough simplicity to them, asymmetrical perhaps, but they are honest and intimate.

Human interaction.

Here is a quote from English writer (and bespoke furniture designer) Andrew Juniper:

"If an object or expression can bring about, within us, a sense of serene melancholy and a spiritual longing, then that object could be said to be wabi-sabi."

Andrew Juniper wrote the definitive book on Wabi-Sabi in English in 2003, ‘Wabi-Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence’.

(Incidentally; I met Andrew Juniper briefly, but sadly we had no time to talk about Wabi-Sabi as he was too busy giving me a short masterclass in how to make the perfect cup of coffee).

Taking time to ponder deeply about the nature of objects, buildings, utensils, we find ourselves perhaps coming to terms with a mixture of wonder and sadness, a resigned reflection on our own transience and vulnerability.

This is a meditation, an interaction with an inanimate object, given purpose and meaning by us.

Why imperfection has value.

To me, imperfection is the antidote to the mechanism of the production line. I think that instinctively we have a mistrust of perfection; we treat the whitewashed wall with suspicion.

Deliberate artful symmetry can be dramatic, but can also lead to blandness and eventually boredom.

If the imperfections and the asymmetry are given space to occur, or the freedom to happen, then the honesty and the rawness comes through.

In a way, the perfection of the factory product had to happen, so that we appreciate the qualities found in its opposite.

Ironically, with Gen ‘Z’, there now seems to be a new-found appreciation of the ‘bespoke’. That generation seem to be always late to the party.

Another example from elsewhere in the world: The roots of early blues music can be traced back to the expert imperfection crafted by the musicians of sub-Saharan Africa.

Look at the way Bluesman Son House treats this instrument. It’s not Andrés Segovia; this is something else:

Musically, the errors are crafted in. But there is a kind of caveat though…

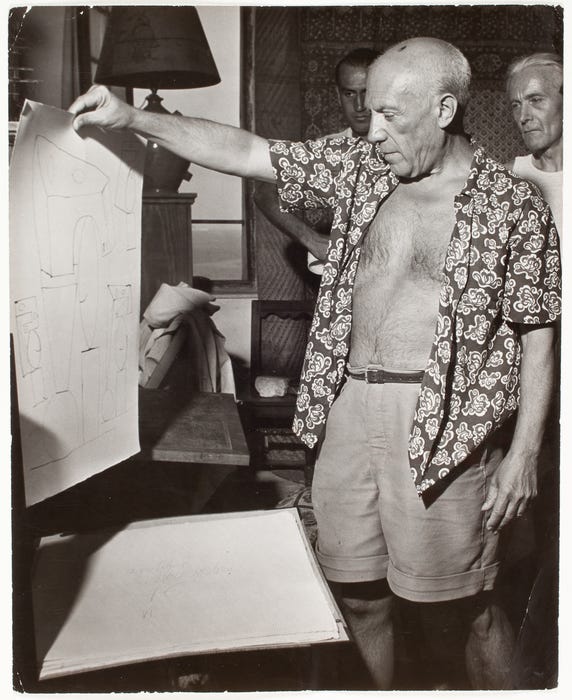

The painter Pablo Picasso did not believe in the ‘happy accident’. A witness saw Picasso clumsily allowing paint to drop on one of his canvases. Picasso looked at it, he liked what he saw, realised that it improved his painting, then wiped it off saying to the witness that any artist worth his salt would have created that ‘accident’. He then painted it back in again.

Credit: The Robert Capa and Cornell Capa Archive, Gift of Cornell and Edith Capa, 2010

The second part to the equation.

The ‘Sabi’ part also has a suggestion that is rooted in impermanence; a kind of forlorn sadness, even wistfulness. But, it is to be tempered with a form of acceptance and compliance to the universal way of all things. Time and timelessness has a part in this.

If we feel so inclined we can add to the mix another Japanese concept; ‘Ichi go, Ichi e’, sometimes explained as ‘this time, this place’. Very similar to the idea that all we have is the present, and as such we should appreciate it for what it is, and value it. But, Wabi Sabi encourages us to meditate on the river of time as well.

Maybe this isn’t just a Japanese thing?

I recently wrote on ‘notes’ that there was no such equivalent in the West. Now I am not so sure. It may not be categorised in the same way, but there are elements in Western culture that have echoes with Wabi Sabi. To explain:

In the West we are not immune to such pondering. There is such a thing as the ‘aesthetic of decay’. This has a long history. The Romantics understood that ruins and forgotten places held a kind of magic. They found beauty in the transient, creating space for quiet, mournful philosophical contemplation.

Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, ‘Monastery graveyard in the snow’.

And we didn’t leave that behind in the 19th century. I am reminded of the photographs of the decaying splendour of metropolitan Chicago by Marchand and Meffre in the early 2000’s. For examples of their work, follow this link: https://www.buildingonthebuilt.org/archive-marchand-and-meffre

Patch and mend.

Another side to this is ‘Boro’. I went to see an exhibition of this Japanese art in London in 2014. Boro is basically patchwork quilts made in northern Japan, constructed from any cloth they had available and added to and passed down through generations. The work in this exhibition included pieces from the 18th to the 20th centuries; all identified by that very Japanese defined palette including indigos, greys and shades of black.

Credit: By Unknown artist - Catalog Photo, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=64429641

Here is a link describing this wonderful exhibition: https://www.houseandgarden.co.uk/article/boro-threads-of-life-somerset-house

Kintsugi.

And then there is Kintsugi; this is the delicate art of repairing broken items, like pots, in an honest way; deceiving nobody, because the repair is very obviously glued/adhered with usually a mixture of gold and resin. Thus, the threadwork of the patching up is almost a celebration of the object and its trials and tragedies. To some it is a metaphor for the human condition. In some ways we are all broken and repaired multiple times. Let’s be honest, nobody gets through life without experiencing bruising or damaging encounters.

Tea bowl, Korea, Joseon dynasty, 16th century AD, Mishima-hakeme type, buncheong ware, stoneware with white engobe and translucent, greenish-gray glaze, gold lacquer - Ethnological Museum, Berlin

Even if you have no interest in the Arts or Japanese philosophy, there is something to learn from Wabi Sabi.

If you want to explore more, you might enjoy this film by journalist Marcel Theroux.

Header image: a much battered and used Japanese rustic arthouse teapot. Author’s own collection.

Thanks Tim, a very enjoyable read - and like you say, a metaphor for the human condition. We should all treasure our perfect imperfections!

I think the older you get, the better able you are to truly understand Mono No Aware and these complex feelings toward the imperfect and impermanent.