The invention of the keikogi.

Have you ever wondered how we ended up wearing those white pyjamas?

To get the answers to this we don’t have to take a deep dive into Japanese history. From my designer background I find this an intriguing story, which also gives a glimpse into Japanese culture.

What the heck were they wearing before the development of the standard keikogi?

To get a grip on this we have to adopt our colonial western goggles.

In the later 1800’s European commentators with a Victorian mindset reported that the Japanese were often presenting themselves, “as naked as frogs”. I suppose that compared to the ‘buttoned-up’ Victorians the Japanese must have appeared more than liberal in their dress code.

Men wore little more than loin cloths and loose open tops; the view of semi-bare buttocks was perhaps too much for matronly aunts?

The design of Japanese garments was not primitive or ‘quaint’, and so it is with the keikogi; which ironically was a compromise between western fashion and Japanese practicality.

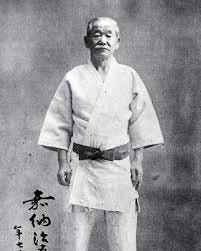

The man responsible – Judo’s Kano Jigoro.

Some time between 1882 and 1889 Kano made a design decision to standardise a practical training uniform for judoka. This was based on three main reasons:

1 Universality, regardless of cost.

Kendo already had training gear; students and schoolkids, who wanted to train, were having to access the armour, hakama, shinai etc, and lug it around, it all came at a price. The Keikogi for judo was deliberately light enough (as was feasible) to just bundle up and launder as needed.

However, there was a wider influence that came from the western ideas of fashion and clothing that were entering Japan at the time.

The predominant white colour was not symbolic, it was just the natural colour of the cotton (and perhaps a useful motivator to keep it clean?)

The uniform made everyone the same; it was supposed to eliminate any hint of status. Over time, master Kano himself wore the same keikogi as even his lowest students.

2 Reputation and forging a brand identity.

This was all part of modernisation. Kano was a progressive and a universalist, he understood how the rest of the world was operating in the fields of sports and physical culture. In the west, teams had identifying kit, standard in colour and design; it made a statement about who they are and what they meant. It still goes on today.

Walk into any sports centre and you can usually see how people are dressed tells you what they are there for. (All those white uniforms; must be some form of karate?)

3 Safety and technical convenience.

There were all manner of design considerations that meant the judo keikogi was going to support the intentions of the practice of the art/sport and make life easier for the practitioner. To explain this in detail it’s worth taking some parts of the uniform to pieces and look at their component parts.

The jacket.

Historically, this was based upon a long-existing outer garment worn as part of standard dress for anyone from farmers to Japanese firefighters; this was the Hanten/Uwagi.

A seventeen-year-old Kano, making a tough aggressive posture, as a pre-judo, old-school jujutsuka, wearing a Hada-Juban, sleeveless outer top.

Kendo guys had already developed a robust cotton version, one held together tidily with ties. These ties would just not work in judo, as the rough and tumble would just tear them off; but karate people kept them, and just changed the position to the side vents (and still they get ripped off).

In judo, the collar and lapel were designed as one continuous piece. This part of the jacket became crucial and enhanced performance and intention (grips on collar and lapel). These lapels were deliberately thick and multi-stitched.

There are surviving examples of jackets belonging to Kano (kept in a museum) and one of his top students, Saigo Shiro, these have amazingly robust lapels, almost like a rope.

Kano’s jacket courtesy of the Kodokan archive material.

I have a memory of an early judo training film where ropes were made out of lapels/collars, which students gripped hard and climbed up, rather like old-style gym rope climbing. Rope climbing is still a thing for judo people, but not the older customised version:

In kendo the sleeves are short, in part to prevent the sword/shinai hilt snagging up the sleeves, which, in swordsmanship could be a life and death thing. There were early arrest techniques which involved incapacitating a sword-wielding opponent by thrusting your weapon, or your hand, up his sleeve.

Kano found that longer sleeves (like longer trousers) helped to limit coarse abrasion from harsh frictional contact with tatami mats - which were not so forgiving as the soft, slick modern mats found in BJJ etc, (but still those guys feel a need for a kind of abrasion-free underwear).

I think it was because in judo they spent so much time in continuous randori; much more than their Koryu forerunners, this was a necessity.

Why did karate go in the same direction?

It’s obviously really; judo as being at the vanguard of progressive cultural thinking was the model for others to follow. If karate wanted to be accepted in the Japanese constellation of institutional Budo it needed to adopt the image of modernisation to be able to present itself to the outside world; and it worked.

Early pictures of Okinawan karate showed them basically training in their pants; rather like Chinese Gung Fu stylists from the earlier era were just in their street clothes (monks were different). The underwear-clad Okinawans needed to get with the picture and modernise if they were to be taken seriously.

The karate keikogi was allowed to be of lighter cotton, not needing to suffer the push, pull and tug of judo. And then came the sash, the obi, the belt.

Belts.

There is a long and complicated history of the belt/sash in Japanese fashion, from the kimono to the kind of ‘utility belt’ worn by the samurai, with its layers and the obvious and hidden weaponry. But it was only with modern Budo that it gained a new significance; one of identification and rank.

Early versions worn by Kano and Okinawan karate master Funakoshi Gichin were just a kind of sash. But, Kano needed to be able to identify the high skilled judo practitioners from the newbies and so the black belt appeared. The multi-coloured belts were actually invented by Japanese judo Sensei in Europe.

In karate, a now very elderly Wado Sensei told me that in his days at Nichidai university the long belt ends dangling down became like a fashion statement, with little utilitarian credentials (unless it’s to have you name etc. embroidered on). So much for anti-status.

I am sure there is a much bigger tale to tell. I wanted to go into the fabric and manufacture, but thought that perhaps it was too specialised a field. Besides, these musing are long enough already. Please feel free to comment below.

Footnotes:

Multi colours.

In recent times, Judo somewhat went against the spirit of the ubiquitous pristine white uniform when it said that modern competitors should now have one white keikogi and one blue, to help judges and competitors understand who is who. The cynic in me wonders whether this idea came from the companies who make judo keikogi, as it doubles their demand and their profit.

Thank you for this insightful piece! I really enjoyed learning about the history of keikogis and how they evolved into what we see today. I appreciate the effort you put into sharing this knowledge and would like to add something about the black hakama.

Early on, Aikido hakama (also used in other martial arts like Kendo and Iaido) came in a variety of colors, often reflecting personal choice or school tradition. It wasn’t uncommon to see even patterned fabrics.

After WWII, Japan was in a tough economic situation, and people had to get creative with materials. Many hakama were repurposed from whatever fabric was available, like old curtains. Since these fabrics were mismatched or had funny patterns, they were dyed dark/black to create a more uniform appearance.

Even worse: many students simply couldn’t afford a hakama at the time. The founder of Aikido, Ueshiba, didn’t want financial hardship to be a barrier to training. So, he allowed students to practice in just their keikogi without a hakama.

Over time, these practical decisions (black hakama and no hakama for beginners) turned into a "rule" - unfortunately. But some traditional (or rather progressive?) schools stick to the old way, where everyone wears one from the beginning... and some even allow all the colors (again).