Takeda Sokaku Part 1.

A commentary on one of the most contentious martial artists of the early modern era.

Header image: An imagined depiction of one of his most notorious escapades (see below).

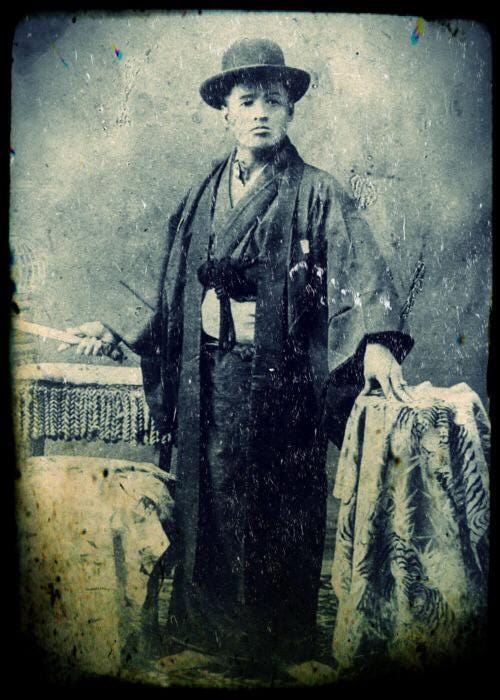

Takeda Sokaku 1859 – 1943.

Reasons why martial artists might be interested in his story:

· Takeda was a cultural bridgehead between the old Japan of the samurai and the emergence of what we call Modern Budo. Many aspects of his life underline the mismatch and conflicts between these two cultures.

· The relationship between Takeda and his more famous student Ueshiba Morihei, who went on to found Aikido from a base of Takeda’s formulated system, Daito Ryu Aikijujutsu. Two martial artists of mythical skill, who couldn’t be more opposite to each other.

· For anyone interested in systems (like me), the way Takeda distributed and promoted his ideas through the school of Daito Ryu is worth unpacking.

· It’s a hell of a good tale.

A daguerreotype image of Takeda Sokaku (Public domain).

The reasons we know so much about Takeda Sokaku are that his life spanned a period where living memory was still reachable to scholars. Fortunately, people who knew Takeda and trained with him were asked to recount their experiences of him.

The late Stanley A. Pranin of Aiki News went after the Takeda story with the passion of a bloodhound journalist and scholar. His writings and interviews play a large part in the content of these pieces.

Ellis Amdur also supplied some fascinating observations, conjectures and analysis of Takeda and his genius, in a very ‘warts and all’ way.

These two sources will be my main inspiration; however, I am aware that Stanley Pranin very much comes from the Aikido camp; while Ellis Amdur is a Koryu specialist, but also with his roots in Aikido. The Daito Ryu angle has not had the same voice that the Aikido people did; so really we have to be aware of whose lenses we are looking through when examining this story.

In much of this tale Takeda gets a bad reputation, certainly his choices are questionable, even by the standards of the day. But you will see that it seems he didn’t really help himself. Whether that is nature or nurture, you can make your own mind up.

Early life.

Born the second son to a samurai farmer in the Aizu Province in 1859, he was shaped in two main ways. Firstly, that he was a fireball of energy that his family couldn’t control, and secondly, his father and other older relatives were martial arts people of the highest skill and reputation, and it was very much a case of channelling him into that tradition.

His training origins suggest a brutal stewardship of discipline imposed on him by his father. From childhood to teens, he experienced a well-rounded, though harsh, martial arts apprenticeship. He once told an interviewer that his father would punish him by burning incense on his thumbnails (with obvious scars to prove it).

He became an expert in the full working arsenal of the traditional samurai’s repertoire (at the expense of any education or schooling; making him functionally illiterate).

Busting heads and brutality.

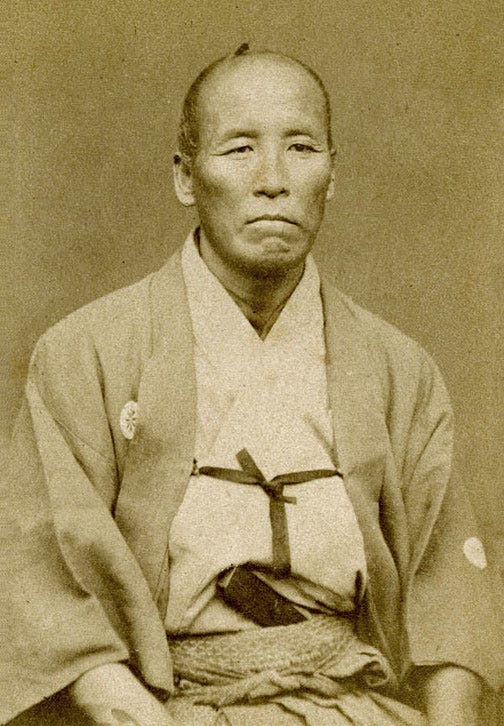

Contests and even duels were part of his teenage years. Very early on he was enrolled in the school of the most famous swordsman of the era, Sakakibara Kenkichi (1830 – 1894). But, despite this discipline and intensity he just seemed to almost willingly run into trouble. He had a nose for it.

Sakakibara Kenkichi, photo (public domain)

On one occasion he accidentally blundered into a night-time skirmish between rival gangs. Caught in the middle, he managed to escape by drawing his sword and cutting the legs of several adversaries and then jumping into a river.

Also, while still a teenager, ignoring all warnings, he marched straight into the middle of a robber’s ambush. Of the three thieves involved, one later died from his injuries and the other two never recovered from wounds inflicted by Takeda’s blade. Clearly, he had no fear when it came to testing himself, and no qualms about maiming or even killing his opponents.

Making a living.

After the Boshin civil war ended, swordsmanship almost went underground and Takeda found a novel way of earning a crust. His physical skills being what they were, he joined a travelling acrobatic troupe.

It was during this period that he is supposed to have had a fist fight with an Okinawan karate expert, and interestingly managed to beat him with superior body movement and evasion which were related to spear and sword techniques.

This seemed to have sparked his interest in karate (or ‘Tode’ as it would have then been called) enough for him to actually go to Okinawa and seek out karate teachers to challenge them. Unfortunately, no accounts survive of his encounters. But, this just goes to show what a martial arts melting pot Japan was at that time.

Takeda’s expertise.

Just what was it that made up Takeda’s skill-set?

It would be fair to say that in his early years his accumulated arsenal was very much Sogo Bujutsu; this was the all-encompassing toolbox of the professional warrior. This included all manner of weaponry skills as well as unarmed or semi-armed techniques which would later fall into the clear-cut category of jujutsu.

Takeda’s primary weapons were the sword and the spear. For those interested in the specific ryu, his main influences were from Ono-ha Itto-ryu, Jikishinkage-ryu, Hozoin spear (there was also some Sumo wrestling in there, which probably has a particular relevance). He had skills in other minor weapons as supplements to his needs.

His sword work is described as an idiosyncratic amalgam; something very much a reflection of his vast experience and exposure to many experts and systems.

The secret weapon.

[To read the remaining half of this article, become a paid subscriber. If you can read beyond this point, that means you are already part of the premier membership, and I thank you for your sponsorship and support of this rather niche area of journalism].