Or none/all of the above.

Probably the most famous samurai warrior of all time, the only one to leap into modern western culture via his musings in a book now known as, ‘A Book of Five Rings’. Appropriated by the business community, it sits on the bookshelves of high-powered CEO’s alongside the ‘Sun Tzu’ and Machiavelli’s ‘The Prince’.

Martial artists and Musashi.

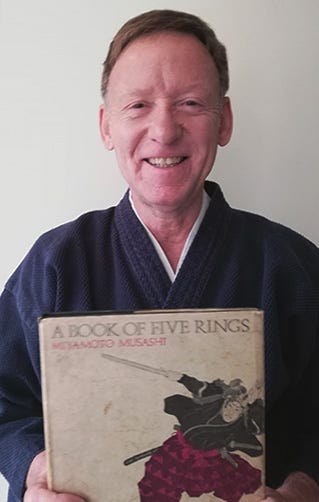

I bought my copy of ‘A Book of Five Rings’ way back in 1978. As a fresh Dan grade, I eagerly pored over the pages hoping to somehow absorb the wisdom that was supposedly contained within. The book reappeared in my life many years later when it was included in the Dan grading exam (an essay needed to be written and this was one of two titles). I did wonder; in a Wado grading exam, why was this book so important? My theory about that was that it wasn’t ‘important’, it was convenient.

It was good to rediscover my original version for writing this piece.

I don’t think we really appreciated the various barriers that got between us eager western martial artists and Musashi Miyamoto, particularly the translation issue. Although, in conversation with one of my university lecturers, he warned me about the reliability of translations, he said, “Translations are like wives; the faithful ones are seldom beautiful, and the beautiful ones are seldom faithful”, he was a product of his time. But misogyny aside, he had a point.

But really, what did I get from Musashi’s writings?

The positives were that he was my jumping-in point to Japanese history, and this then lead me on to other books (although it has taken a very long time for Japanese translated books to make it into the English-speaking world).

I also found some wisdom in his generalism and broad-brush approach, the way he could apply the same principles for large and small scale engagements; it was a clever device, but I realised later on that this same logistical tool appeared in classical Chinese philosophy (Taoism and Confucianism).

As a martial artist, there was something there about strategy and trickery, but, in all honesty, other wisdom had to be teased out of the text, more implied than directed. Yes, there were examples, all of which related to swordsmanship and obviously clear links to Zen thinking (although I think Takuan’s words on Zen, the Mind and swordsmanship dig much more deeply).

The other main barriers were historical and cultural.

Judging Musashi by our own standards.

One of the big things about history is that we tend to judge people and events through our own modern lenses. It’s really difficult to climb inside the head of a warrior from the 16th century, and even more of a problem if they existed in a culture so far removed from our own. Even, modern Japanese culture is so full of contradictions and illogical modes of thinking that become unfathomable to Westerners; project that back into those times and it becomes almost impossible.

Taking a few basic stories from his life and you might come up with the viewpoint that Musashi was drawn towards murder, the early Japanese Hannibal Lecter. It was almost as if there was a list inside his head of people who just needed killing, and he was the man to do it. Note, this is not bandits (as in the Seven Samurai) or other morally reprehensible villains; some of his victims were mere teenagers.

I give you the example of a feud. When Musashi was twenty-one, he went to Kyoto where he became embroiled in a vendetta against the family sword school of the Yoshioka’s.

In duels he humiliated their main champion and then killed the second by crushing his skull with a bokken. The final challenger was a mere boy, not yet in his teens, who turned up to the appointed venue with an armed retinue. Musashi remained hidden until they thought he was not going to show, and then he leapt into the middle of them and cut the boy down, and then had to fight his way out.

Musashi had around sixty duels by the time he was twenty-nine. He wandered, almost aimlessly. His reputation became legendary; many stories were told about him and it is said that some of the various Lords and Daimyo’s would not employ him. It didn’t help that he was known to be scruffy and unkempt, refusing to enter bathhouses for fear of ambush. One source says that the reason for his appearance was a skin condition, but who can sort fact from fiction?

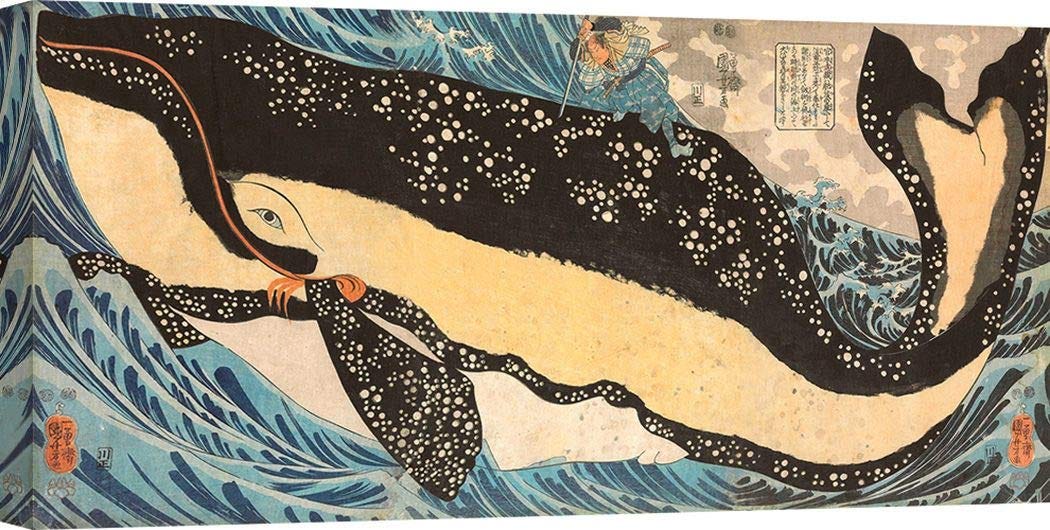

Kuniyoshi’s depiction of Musashi killing a whale… well really?

There seemed to be no real evidence of a romantic involvement in his life, although he wasn’t to remain totally solitary. There is a record of an adopted son and, in later life, sword pupils who were very loyal to him. The impression I get is that he had so much knowledge to offer, his approach being so unorthodox (famously, his preference to fight with a sword in each hand).

What comes across in the book is that he seemed to have a later life epiphany when he realised that expertise in a wide field of human activities all shared common principles; thus, a deep dive into any art or skill opened the door to all of the others. He could draw direct lines between carpentry and swordsmanship. This revelation gave him full licence to explore other art forms, for example; he was known for his painting and ink work, wood carving and calligraphy, even the crafting of sword furniture (the hand guards and fittings).

Once he’d left the role of lone wolf killer and settled down with some sponsorship behind him, he was able to explore these options. Without that stability we would never have read his words in ‘A Book of Five Rings’.

To round off.

Does he deserve our adulation? When I started writing this piece, I was quite dismissive, but as my research developed (and rereading ‘A Book of Five Rings’) I have warmed towards him. And as for his morality… He was a product of his time, of the practicalities of a ‘live or die’ reality. I have to remind myself, he was at the monumental battle of Sekigahara in 1600 (body count, possibly 120,000) and later in life, he was an officer involved in the slaughter of 37,000 Christians in the Shimabara uprising of 1638. This is a world of blood and gore we have no way of understanding.