In this first part:

· Suzuki Sensei introduces Mokuso.

· How did it work?

· The Keisaku.

· Breathing and the mind.

· The pain.

· The meditation stool (a failed experiment).

Early 1980s; an English seaside resort in high summer.

A solitary holiday maker allows curiosity to get the better of him and ventures through the open doors of a large airy civic building. This is a typical Victorian edifice normally used for concerts and other large public gatherings.

The inquisitive tourist’s eye is caught by a peculiar sight.

There, in the main body of the building are seemingly endless rows of people dressed in white, kneeling ceremoniously, all stock still and totally silent.

The mid-morning sun sends shafts of light across the room, the only barely perceptible movement is the gentle rhythm of collective breathing.

This scene remained largely undisturbed for nearly thirty minutes. What was going on? What was all of this about? Did it serve a particular purpose?

Now a view from the inside:

My personal experience of the practice of Mokuso, a kind of meditation which acted as an introduction to each day’s training on the Wado Ryu karate Summer Gasshuku.

Although the daily training had a reputation of being notoriously tough, it was the comparatively tranquil practice of Mokuso which for some people held the most dread. It almost assumed a mythical status and, as a tradition became an established institution which to the majority of participants became synonymous with one thing…pain.

Martial artists Western and Eastern are not known for showing their antipathy towards suffering and discomfort, instead steely stoicism is the order of the day, but with Mokuso there were no restraints and the groans and grumbles continued unabated.

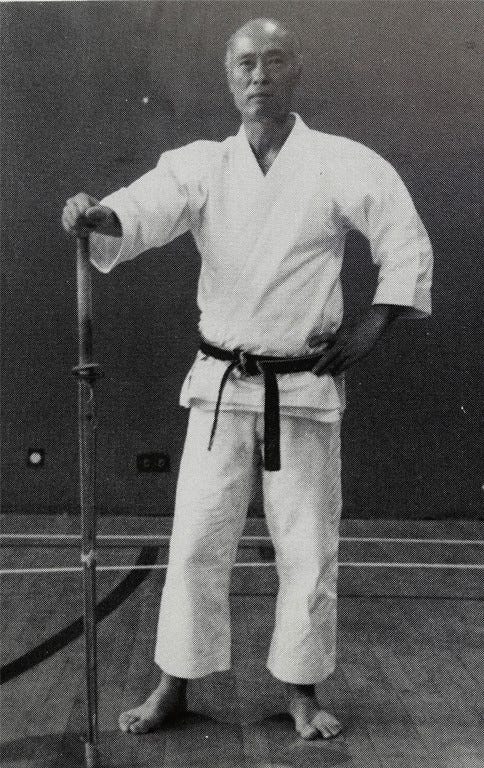

In these times the late Master Suzuki Tatsuo Sensei 8th Dan Hanshi presided over the week long Wado Ryu karate summer courses (Gasshuku). It is just possible that because of his own experiences in a Zen monastery in Japan in the mid-1950s Suzuki Sensei thought that establishing this seated meditation in regular practice would enable the Westerners to add something of value to their training.

If my memory serves me correctly Suzuki Sensei did not introduce this practice consistently at the beginning, and it took a while for it to become consolidated.

So, how did it work and what were the procedures?

At the start of training the students were lined up in order of seniority; highest grades at the front, an intimidating position to be in as you found yourself directly facing the senior Japanese Sensei. I often wondered if those at the back were allowed greater leniency as they were the least experienced and further from the critical eyes of the Sensei.

However, at a significant juncture in the meditation session Suzuki Sensei would rise and quietly pad over to retrieve a Shinai (Bamboo Kendo fencing sword) and would then prowl silently between the rows.

Suzuki Sensei and his famous Shinai.

This automatically caused backs to stiffen and chins to tuck in, this was because we had all previously received detailed instructions of how we were to conduct ourselves during Mokuso.

The back must be ramrod straight, the eyes half closed and whatever happens you must not move or fidget. This meant that if your mind wasn’t settled and, (according to tradition), you needed to be ‘reminded’; the person overseeing practice would feel compelled (duty bound) to correct your shortcomings.

If Suzuki Sensei saw someone not complying, he would walk across to them and, with a gesture, ask them to lean forward, and the Shinai would descend three times and connect sharply with their shoulders and back. Listening to it, despite your best efforts, it was impossible not to wince at the sound. To the outsider this practice may seem to indicate a certain level of cruelty, but looking closer at the cultural background there might be more to this than meets the eye.

The stick of ‘awakening’.