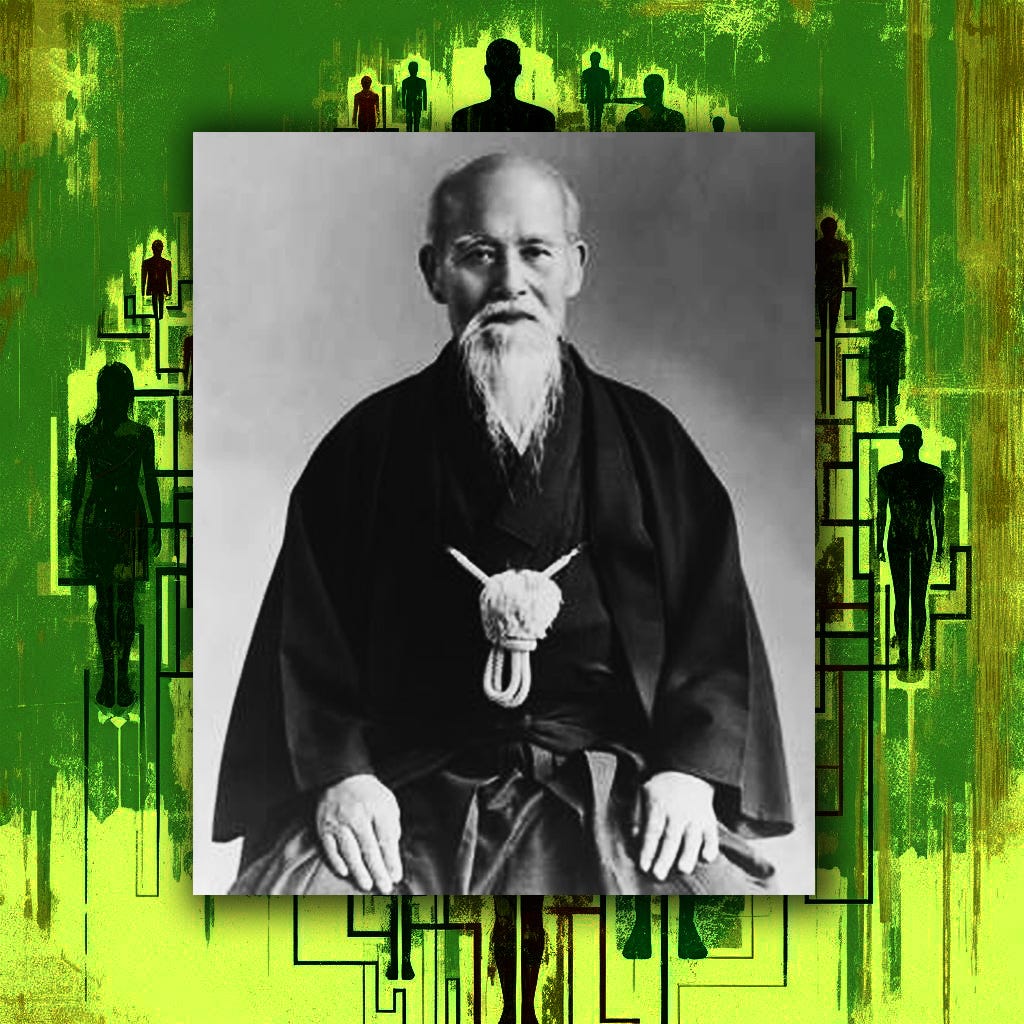

Header image; Ueshiba Morihei Sensei (1883 - 1969) Founder of Aikido.

In this final part; keep at the back of your mind these two continuing threads (it will help readers understand the framework of what I am exploring here).

1. The three-generation rule.

2. Iemoto (Family lineage passed on).

Content:

· The adopted son.

· Aikido.

· A brief note about Wado Ryu.

· Shorinji Kempo.

· Conclusion.

Adoption and non-familial transmission.

I don’t want to drift too far off my ‘keep it in the family’ theme but, what if the family pass on the tradition outside of the family; including adoption?

The ‘adopted son’ concept is something found all over the older Japanese martial traditions. Sometimes a promising student will be encouraged to marry into the family to make things easier to pass the lineage on to him. The Japanese do not seem as up-tight as westerners in these things. Modern westerners seem unconsciously aware of blood and genes; perhaps because science has influenced our thinking for much longer than in Japan (there may also be biblical and other cultural reasons).

Also, outside of my current remit, clearly; it’s not compulsory for the traditions to go through the family line, but I want to stay with my theme.

What about the current generations of family traditions in the broader Japanese martial arts?

Aikido.

Aikido seems to have reached its third generation:

· Ueshiba Morihei (1883 – 1969) First generation and founder.

· Ueshiba Kisshomaru (1921 – 1999) son of the above.

· Ueshiba Moriteru (1951 to present day).

Lined up is potentially the 4th generation; Ueshiba Mitsuteru, born in 1981.

The progression from Morihei to Kisshomaru is an interesting one, something that throws up the issue of generational responsibility.

Put simply; Ueshiba Morihei was a martial artist of almost God-like ability; his son was always going to find that a difficult act to follow. (I would actually say; not ‘difficult’ but impossible). This is an extreme example that appears with other ‘second generation’ family inheritors (see below).

A basic Googling around reveals that there was disquiet when Kisshomaru took over the running of the firm. There were those who said that his emphasis on a particular style of teaching suppressed the idiosyncratic nature of Aikido, and alternative interpretations were not given the credit they deserved.

In part, I am sure that comes from the mercurial nature of the system and its original founder. Kisshomaru was always going to struggle with that.

An early 1957 film of Ueshiba Kisshomaru, son of the founder and second-generation inheritor:

Wado Ryu second generation.

An interesting case with Wado Ryu Karate-Do and the second generation. Otsuka Jiro Sensei (who took his father’s name/title and called himself, Otsuka Hironori II), said on one of his UK courses that he did not have one-eighth of the ability of his father, Otsuka Hironori, the founder.

(Interesting that he should come out with such a strange number – maybe it’s a Japanese thing? Such as, the significance in the far east of the number 10,000, generally just a way of saying ‘many’).

This was a statement of modesty, as well as one that elevates his late father’s status. I understand why he felt it necessary to say that.

Film of the first and second generation of the Wado Ryu:

Wado is also currently on its third generation. Present head; Otsuka Hironori III Sensei (Otsuka Kazutaka).

Other problems inherited by the second-generation son.

It is worth noting at this stage that the second-generation son often seems to suffer badly at the hands of the older conservatives within the system; who frequently make a sport of turning the inheritor into a favourite whipping boy, frequently through whispering campaigns, or even out-and-out break-aways. Normally this can be seen as pure politics; likely emanating from bitterness directed at the Iemoto system.

Of course, the other school of thought is that the generations that follow are mere shadows of the first generation; which in its own way becomes ammunition for the critics. So, often it is really difficult to separate fact from political fictions.

If you take the long view and curb your tribal instincts you can see it for what it is. It follows the applying of the phrase, ‘Cui bono’, ‘who benefits’?

Example: If you are an old-timer who’s dwindling authority comes from your contact with the first generation, of course you are inclined trade off your seniority, and perhaps disassociate the connection with the second generation.

Shorinji Kempo, another example.

Shorinji Kempo is a kind of hybrid Japanese martial arts system, very difficult to categorise. Founded in 1947, it stands out among the other modern styles. Part karate, part jujutsu and supposedly part Chinese Chuan-fa. Is it a religion, is it a cult (in Robert Twigger’s book ‘Angry White Pyjamas’ a ‘friend’ describes it as such – I couldn’t say). Or is it just a well-marketed business? (Current membership figures says 1.5 million members in 33 countries, that is pretty impressive).

If you are curious as to what it looks like: Shorinji Kempo Embu:

Founder.

Shorinji Kempo is the invention of a character called Doshin So (a.k.a. Michiomi Nakano) 1911 -1980.

The origins story is fraught with information that struggles to be verified, but it is generally told that Doshin So spent considerable time in Manchuria and China, partly within the Japanese military framework. The Japanese clash with Russia and the general murkiness of what was happening in that part of the world makes it tricky to define just exactly what was going on.

The story, from Shorinji Kempo sources, tells us that Doshin So inherited a form of Chinese Gung Fu supposedly directly connected to the Shaolin Temple in Hunan and claimed to have visited the temple and was inspired by the murals of monks training. This suggests that Doshin So travelled huge distances in China.

Doshin So was also connected through various individuals to the paramilitary ultranationalist group the Black Dragon Society, which had its roots in the organisation, the Gen'yōsha, which was known as a hotbed of criminality. The Black Dragon Society, did its best to clean its act up and became very well connected in the higher tiers of Japanese government and military. So the embryonic Shorinji Kempo (roughly translated as ‘Shaolin Fist method’) was well situation to take advantage of the various relationships between individuals in the group. In part, like most of my other dynasties stories; high level sponsorship was important if you wanted to get your project launched.

And so, growth took off from that point.

Shorinji Kempo generations.

The second-generation mantle was passed on to Doshin So’s daughter, Yuuki So, who, in part, was a kind of acting president and figurehead. It is said that she only trained for a short period of time, because of injury.

Yuuki So retired her leadership position in 2000 and passed it on to her son Kouma So, who is the current head. This clearly hits the three-generations mark.

The usual problems.

Reading around the subject; Shorinji Kempo seems to have had difficulties that are ubiquitous with other dynastic and global style groups. One of those is over-reach. Global organisations tend to have real trouble controlling their entity once they go worldwide. Adding to that; sometimes the development of stylistic splits leads to messy cases of branding and legal shenanigans over logo and name usage, it’s all so very commonplace.

With Shorinji Kempo there have also been mutterings related to the Iemoto tradition, again, very predictable.

But also, critics have wondered about inclusivity, particularly related to the religious side of Shorinji Kempo, being very clearly Zen Buddhist in orientation. As we know, religion can be blighted by dogma and inflexibility. It’s not always easy to get everyone singing from the same hymn-sheet; or any hymn-sheet at all.

Summing up.

The cynics might say that dynastic inheritance of skills like martial arts traditions would inevitably lead to degradation, dilution, fragmentation and generally losing touch with the intentions of the original founder.

But I am not so pessimistic; there is no hard-written rule that says that the systems have to decline in such ways, or that it always happens over three generations.

It is entirely possible that the inheritors (family members or not) will pick up the original ideas and develop them to even greater heights. As an example, I am fairly certain that within the tangled roots of Japanese Budo/Bujutsu, innovators of subsequent generation have picked up the threads and woven them into something more defined and substantial, without loosing the originator’s core ideas.

Also, generationally, the inheritors are often the closest of all live-in students, so if anyone is going to get a shot at passing on the fuller tradition, including the most closely kept secrets, it’s likely to be them.

The three-generations rule has its uses; it tells us something, but it is really too simplistic a model. What it does shine a light on though, is that although we want to believe that the aspiration of each generation is to do better than the previous generation; it can actually go both ways. Dynasties rise and dynasties fall (a lesson taught to us in Shelley’s poem ‘Ozymandias’).

As for society in general….

In the west, when we look at our own families and the generations that preceded us, we want to believe that we will be healthier and wealthier than our grandparents. Social mobility is a reality, but it is a ladder that leads down as well as up. The current reality is that youngsters today are generally in a far worse position than their ‘boomer’ grandparents.

The whole thing is a living dynamic, and it’s worth digging into, or even taking the long view. In a way, the majority of people who are reading this have either experienced the generational legacy first-hand, or possibly even being the victim of its degenerative aspects and experienced the rise, decline and fall of the generational ladder.

I know there is more to say on this subject, but for now I am parking it here. Please feel free to add your opinions and comments below.