To understand where I am coming from on this; please read part one, where I present the ‘three generations’ model. With the examples given across these articles it may be possible to read the runes, as history repeats itself. This can also apply to newer traditions, or may even act as a warning from history, particularly for those for whom the burden of having to carry a tradition forward is perhaps weighing on their shoulders.

Case 2. The Yang Family Tai Chi.

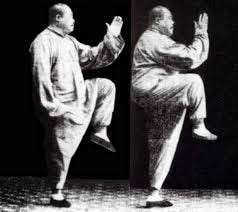

The first three generations: Top; Yang Lu-ch’an. Middle, the sons, left, Yang Chien-hou and right an image supposed to be Yang Pan-hou. Bottom, third generation; Yang Chengfu.

Just as fencing is not my zone, I have to confess my own ignorance of Tai Chi, but reading around the subject over many years I now see that their dynastic history meshes well with the ‘three generations’ theory and has parallels across other martial arts dynasties.

The family inheritors of the Yang family tradition are still around, but Tai Chi as an entity has diversified into so many different modes that it has just become lost in a crowd within a crowd. Firstly, in the vast plethora of martial arts in the current marketplace, but also within the Wellness community, and I can add to that the Tai Chi diaspora itself. It’s a confusion of lineages, dilutions, blends, East versus West, the battle for credibility – I could go on, but, for the sake of my argument I will stick with the Yang’s.

First generation. The springboard; Yang Lu-ch’an (1799 – 1872).

Historically, a similar timeframe to the previously-mentioned Angelo dynasty, but at the other side of the world.

Firstly, anything written about Yang Lu-ch’an cannot be really verified; so much legend, propaganda and politics that everything seems to disappear into the mist. But I will try and give the general story and hope that it is acceptable.

It seems that Tai Chi (Yang family), like many iconic Chinese martial arts systems emerged out of mystery and obscurity in the hands of one pushy, driven, ambitious, enthusiastic individual, who ‘went to the city’ to prove himself as a supreme fighter. It sounds fanciful, I know, but behind all the propaganda and the building of the legend, Yang Lu-ch’an was that individual.

Bear in mind, there are other branches of Tai Chi, so I am not saying that the Yang’s have the full and total authority.

Who knows what the real story is; but basically it runs like this:

Origins story.

Young guy from the sticks turns up at a village and discovers it has an in-house secret martial arts system. Yang Lu-ch’an works his way in and ends up as a skilful master of the art that later came to be known as Tai Chi.

We all have an image in our heads when we think of modern Tai Chi, but the slo-mo calisthenics in parks, under trees in the early morning does not really help to describe what’s going on. Whatever people want to call it, be that an ‘Internal system’, the ‘needle hidden in a ball of cotton’, or ‘soft boxing’, there’s something about it, in a ‘no smoke without fire’ way. Whether that original fire still exists I am not qualified to comment, but it does intrigue me. (I did try it once, but I didn’t inhale).

Yang Lu-ch’an in the city and Imperial court.

It seems that Yang had to be given the blessing of his teachers to go to the city and reveal the secret. Whether he was seeking glory, fame or financial gain it’s difficult to tell, but he succeeded in all of those.

Sponsorship in high places (like Domenico Angelo) unlocked many doors, but also in that environment, it meant that he had set himself up as a marked man. For other aspiring martial artists in the capitol, Yang Lu-ch’an’s scalp had real currency. He never faltered in that area, so this boosted his credentials even further.

Echoing the Angelo’s, Yang was commissioned by the Imperial family to teach martial arts to the elite palace battalion of the Imperial guard. Yang enjoyed the fruits of the extensive palace network; but it wasn’t to last; times were going to change but it wasn’t Yang Lu-ch’an that had to experience what was to come – it was the next generations.

Yang Lu-ch’an’s family inheritors.

The next generation were two of Yang’s sons; Yang Pan-hou (1837 – 1890) and Yang Chien-hou (1839 – 1917).

An interesting myth about these two brothers relates to the training regime their father used to bring them up to scratch as worthy and credible inheritors.

So severe was their training that it is said that Yang Chien-hou tried to commit suicide and Yang Pan-hou actually ran away from home. Whatever was the events surrounding these acts of rebellion, it’s clear that both of them returned to the programme.

As a teacher, Pan-hou was supposedly a hard taskmaster, the impression I get was that he cared little for any kind of compassionate approach; while his younger brother was more of a jolly character who enjoyed popularity. It was one of Chien-hou’s sons who was to pick up the mantle for the third generation.

Yang Chengfu (1883 – 1936) Third generation.

It’s worth now picking up on how things were changing at the centre of power at the court in Peking. These were the declining years, the time when empires slip into decay. The corpse of Imperial China was being nibbled at by Western powers, who had been circling like hyenas for decades. The real collapse happened in 1900 with the Boxer Rebellion. The impact of this was that the gravy train that the Yang’s had been used to enjoying suddenly hit the buffers.

Imperial troops in 1900. Image courtesy of the Army Museum.

But, as with Harry Angelo and the old-style samurai, the Yang’s had to democratise and commodify their one significant asset and open it up to the public, not just the palace dukes and princelings.

Yang Chengfu must have witnessed all of this being twenty-three years old at the time of the Boxer Rebellion. He was in the middle of the change (his uncle, Pan-Hou, had died ten years before these events, while his father, Chien-hou, was also in the centre of this survival crisis). One writer said that the Yang’s were, ‘out on their ear’, but, even as a commercial enterprise they had kudos.

As a family business, they had to be flexible and I get the impression that at no time were they ever to suffer any significant hardship; or if they were, it didn’t last long.

Yang Chengfu.

Yang Chengfu was an interesting character. He seemed to have enjoyed the benefits of the good life. All photographs of him show he was a big guy, burly, but overweight (some sources said he was about 300lbs). Chengfu was a populariser and adapted the system through his own ideas. It has to be said that those who learned from him were generally able to take the credibility of Tai Chi forward into the new age.

Storm clouds.

After the collapse of the Chinese nation everything was up in the air and it all kicked off around 1927, when the country erupted into civil war. This was the beginning of Chairman Mao and the rise of the communists.

The Yang’s seemed to have danced around the political upheavals of the Republican era and took advantage of the urge to elevate the image of China by promoting the exercise and health of the nation through martial arts-based training.

As far as I can figure out Yang Chengfu taught at the Beijing Physical Culture Research Institute from 1914 to 1928, as well as other locations in the south, and then, possibly because of political pressures, moved the Shanghai in 1928.

Many Chinese masters fled to places like Hong Kong, Shanghai and Taiwan.

In his later years Chengfu must have experienced aspects of this upheaval; but, that is a little misleading, as Chengfu didn’t really have the luxury of ‘later years’; surprisingly, as a proponent of a system that is supposed to promote longevity, Yang Chengfu died at the age of 53.

There are many rumours about his early death, some of them put about by people who wanted to pour scorn upon his name, but it just seems to be down to bad luck. The official line is that he was struck down with dysentery while journeying to Southern China in 1936. It’s such a banal and commonplace ending that to my mind, it has to have a ring of truth about it.

Developments.

The general theory is that Yang Chengfu adapted the art of the previous two generations to make it more accessible for the general public. He developed a model called ‘large frame’, with bigger movements of hands and legs.

An early first-hand witness account of what the Yang family Tai Chi looked like prior to the simplification and popularisation comes from the writing of Gu Liuxin describing Yang Chengfu’s older brother Yang Shaohou:

“He used, “a high frame with lively steps, movements gathered up small, alternating between fast and slow, hard and crisp fajin (power/energy), with sudden shouts, eyes glaring brightly, flashing like lightning, a cold smile and cunning expression. There were sounds of “heng and ha”, and an intimidating demeanour. The special characteristics of Shaohou’s art were: using soft to overcome hard, utilization of sticking and following, victorious fajin, and utilization of shaking pushes. Among his hand methods were: knocking, pecking, grasping and rending, dividing tendons, breaking bones, attacking vital points, closing off, pressing the pulse, interrupting the pulse. His methods of moving energy were: sticking/following, shaking, and connecting.”

Yang Chengfu clearly had a method of transmission in mind, as he must have been aware of his legacy and responsibility. He did publish two books under his own name; one in 1931 and other in 1934. Again, this was designed to promote and spread the Yang branch of Tai Chi wider than the borders of China, but still along the lines of the Chinese diaspora (I suspect that at that time the concept of teaching Tai Chi to foreigners was unthinkable, given all the bad history between China and the West).

Image from Yang Chengfu’s publications.

Subsequent generations.

It seems that the Yang family lineage continued forward into the current generation. But, Tai Chi traditions have been subsumed into the complex sea of all the martial arts that exists out there in the wider world. Individual characters, whether they are the inheritors of a system or not, just get lost in the clamouring crowd.

You have to have a kind of advanced publicity machine to appear head and shoulders above that particular maelstrom; I can think of one particular family tradition (nothing to do with Tai Chi) that recently managed to achieve just that; but more of that later.

What would be really interesting would be to know more detailed information about the Yang family’s fortune and status over the generations. I wouldn’t doubt that there were intense political pressures over their professional and social position in a Chinese society that was going through the most extreme upheaval. Add to that series of famines and floods in the late 19th and early 20th century; how did any families, never mind families of status, navigate those catastrophic events?

To conclude…

A comparison with the Angelo dynasty in the UK makes the fencing family’s ups and downs not so very dramatic as, England at that time suffered relatively few earth-shattering events, at least compared to how things were going in China.

Information on the Yang family credit to many sources but particularly Douglas Wile’s book, ‘Tai Chi Touchstones: Yang Family Transmissions’.

In the next part, a whistle-stop tour through another martial arts family dynasty and how it matches with the three-generation rule… or not.

Next stop – The Gracie’s.