How martial artist cope, or don’t cope, with injury.

Observation on martial artists and the catastrophes that befall them.

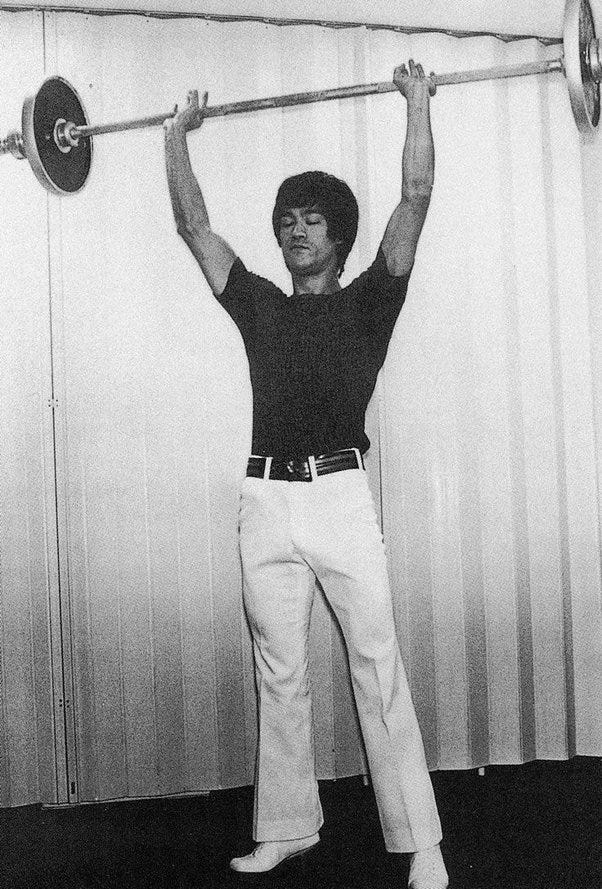

In 1970 the rising superstar and soon to become Hollywood martial arts legend Bruce Lee suffered a catastrophic injury that really should have ended his career.

Lee was working out with barbells performing a manoeuvre with a weight across his shoulders, a particular stress-bearing exercise called ‘good mornings’, a kind of straight-legged hinge. Most trainers would advise against this exercise unless you really know what you are doing, the potential for back injury is notoriously high.

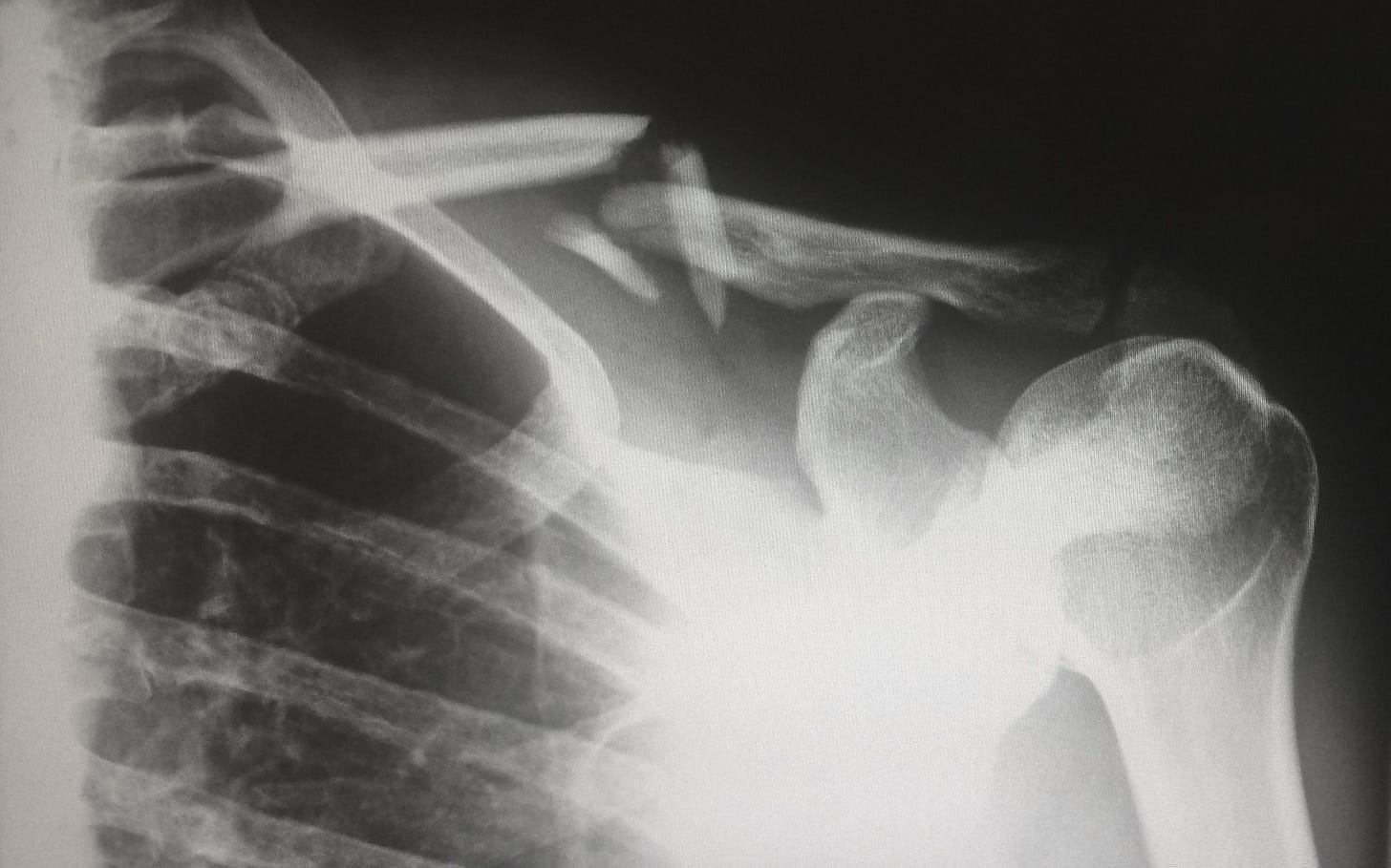

Lo and behold this was exactly what happened. The general story goes that Lee experienced immediate pain in the lower back. Doctors at the time diagnosed damage to the 4th sacral nerve. It was so severe that he was bed-bound for a very long time.

For Lee, the timing of this couldn’t have been worse and for someone whose whole life, future and career was wrapped up in his physicality it looked like the worst of all nightmares.

The Bruce Lee legend and mythology insists on telling us that his energy and will could not be defeated etc. etc. What is certain is that he did utilise his forced incapacitation fruitfully and used the time to study and write about philosophy and his ideas on the martial arts. His jottings were later collated into a book that appeared in 1975, two years after Lee’s death, titled, ‘The Tao of Jeet Kune Do’.

Lee is said to have ‘recovered’ by applying his intelligence to his rehabilitation, but the real story is that although he became functional again over time, he was never able to eliminate chronic back pain. How modern surgery might have helped Lee to recover is an interesting speculation – medicine has moved on a long way since 1970.

I use Bruce Lee as an example of martial artists who suffer injury either accidentally or through their own fault, by either being unlucky, or, as in Lee’s case, reckless, spurred on by an overwhelming feeling of overconfidence to the level of believing in his own indestructible nature… reality check for Bruce.

But, for anyone to be struck down in such a way, particularly if their whole being is invested in their physical prowess it is a complete tragedy and you’d have to have a heart of stone not to feel it, particularly if there is no coming back from it.

A few years ago, I listened to a radio documentary about dancers and injury, in which it was said that unlike normal mortals dancers die twice. It told the story of a dancer at the top of her career who, in the process of just walking off stage, felt her leg just ‘go’ and she knew straight away that her dancing career was over, she had experienced the first ‘death’.

After watching the Netflix three-part documentary ‘McGregor Forever’ about MMA fighter Conor McGregor, and seeing within the first five minutes of episode one a slow-motion close-up of McGregor just seeming to step back in the ring and then his ankle just snapping (not for the squeamish), the same thought about dancers ‘dying twice’ came to mind. In fact, one of my abiding impressions of the McGregor documentary was that for all his optimism he was no stranger to injury, but, in that high-powered level of physicality you’d have to say that over time something’s gonna give.

Many years back, I read Neil Adams’ autobiography of his life in Judo, I came away with a view that the attrition rate at Judo is also inclined to be pretty high; tales of shot knees, messed-up shoulders abounded. Some good news for Judoka (although, until I read about the evidence, I thought this was a myth) apparently older Judoka tend to have much higher whole body bone mineral density than other athletes. The suggestion seemed to be that all those years of being pounded into mat had created an accumulation of pressures that resulted in a measurable physiological change – the same goes for wrestlers, apparently.

How much pressure can the body take? Someone once told me that the majority of sailors in Nelson’s navy suffered from hernias; this was as a result of the physical demands of just pulling on ropes. From the things I have read about the survival rates in the British navy in those days, I think herniation would have been the least of their problems. But it goes to show that however tough we thought they were, they were not immune to physical hardship and the body not being able to cope with the pressures.

But what about coming back from injury?

In the modern world we are much more knowledgeable and well-informed about the avoidance of injury and the treatment and recovery necessary to repair and heal. But sometimes the problem is that we are dealing with martial artists here. I can think of many instances of martial arts people who suffered injury but put themselves back into training too early and either set the project back by being reckless and gung-ho, or just blew the whole thing in one mad splurge of over-confidence.

Back in the 1980’s there was a very promising British competition fighter from my area who had made his way into the England team, Gareth M, his star was on the rise until a clash resulting in a broken femur spectacularly laid him low. I am assuming that he was given the right advice, but youthful enthusiasm got the better of him and he returned to sparring far too early, consequentially he broke the same leg again – net result, equals, end of career.

There’s a bigger story to be told about the vulnerability of the athlete and whether the whole thing is just a lottery and our flirtations with risk are putting us in harm’s way; but, as a counter to that, you can’t encase yourself in bubble-wrap.

Old Wives Tales.

Another piece of mythology that is not supported by research. It has always been said that sportspeople are inclined to be more healthy based on data that says they just don’t go to the doctors as much as non-sportspeople. This might be true, but digging into the research the reason they don’t seek medical advice for aches, sprains and pain is because their sporting careers have given them a higher tolerance for pain. At this level, they are just the same as everybody else. How that works with things like degenerative disease etc is a bigger thing.

The whole ‘ageing’ thing.

It can be a depressing experience getting in amongst a bunch of ageing martial artists when they are talking about their injuries and ailment, but certain cautionary tales can be gleaned by any youngster who happens to be listening in.

The first message to youngster is that you are not invincible. And the second observation is that often old injuries come back to haunt you, even long after they seem to have recovered, they seem to set-up weaknesses in those areas that then act as a springboard for other ailments.

Also, many of us have had our most significant injuries NOT from martial arts but from other sports. The confidence you get from martial arts training does not always crossover to other activities. Competence in one area does not always equate to competence in other areas.

I have accumulated injuries from various activities including, squash, rugby, football, American football and, one of my worst injuries that took years to shake off, from diving for a catch in softball.

Of course, age makes you more vulnerable. The types of smart supplementary exercises a 50 year old might do are not the same as they would have done in their 20’s, there’s a different agenda running.

To keep it very basic, it is my belief that there are two forms of exercise that give the older martial artist the best results in terms of avoiding further injury:

1. Resistance exercise to maintain supportive muscles around structures and joints. As you lose elasticity and flexibility in supportive tissue the strength element needs to be there to bail you out if you suddenly find yourself in unfamiliar ranges of motion. In those circumstances the muscles and tendons might struggle to find the flexibility to offer any kind of support, resulting in injury. Or, the body will recognise that it is moving into an unfamiliar zone and snap on the brakes; a bit like an inertia reel seat belt, but if the muscles aren’t well maintained and have been allowed to weaken, it won’t be enough, and damage will ensue.

2. Core exercise. Nothing will mess you up like a weakening core. Posture goes, bad habits sneak in (observe yourself as you get out of a chair) and then along comes the unexplained back injury to really rain on your parade. All as a result of a neglected core.

Alas for poor Bruce Lee; it was a rare reaction to analgesics that finished him off and resulted in his death at the age of 32. A tragic twist of fate.

Photo by Harlie Raethel on Unsplash

Bruce Lee image credit: Quora.

Martial artists, for better or worse have a tendency to have this indomitable spirit about them and will power through injuries that they really shouldn’t be powering through.

Throughout my career I’ve been careful to push myself but not past the point of doing permanent damage stressing your body can lead to some incredible adaptations. Stressing it to the point of breaking can lead to injuries you’ll never truly recover from.

I think some injuries in karate especially hips knees are westerners trying to kick too high, falsely thinking that's a necessity. When it's not. Far better is to teach and learn correct technique, and accept your body limitations. Then focus on getting that best you can. Constant repetition, seeking the impossible, that's the secret. To me anyway.