19th century European painters have more than their fair share of Bohemians, wild boys (and girls), eccentrics and geniuses; but you don’t tend to think about that with the Japanese. Let me tell you, they are definitely there.

Hokusai was, in his generation, the best of the best. In fact, his sparkling and dramatic artworks have continued to ripple through time; very much like his iconic ‘Great Wave off Kanagawa’ (1831) [Header image].

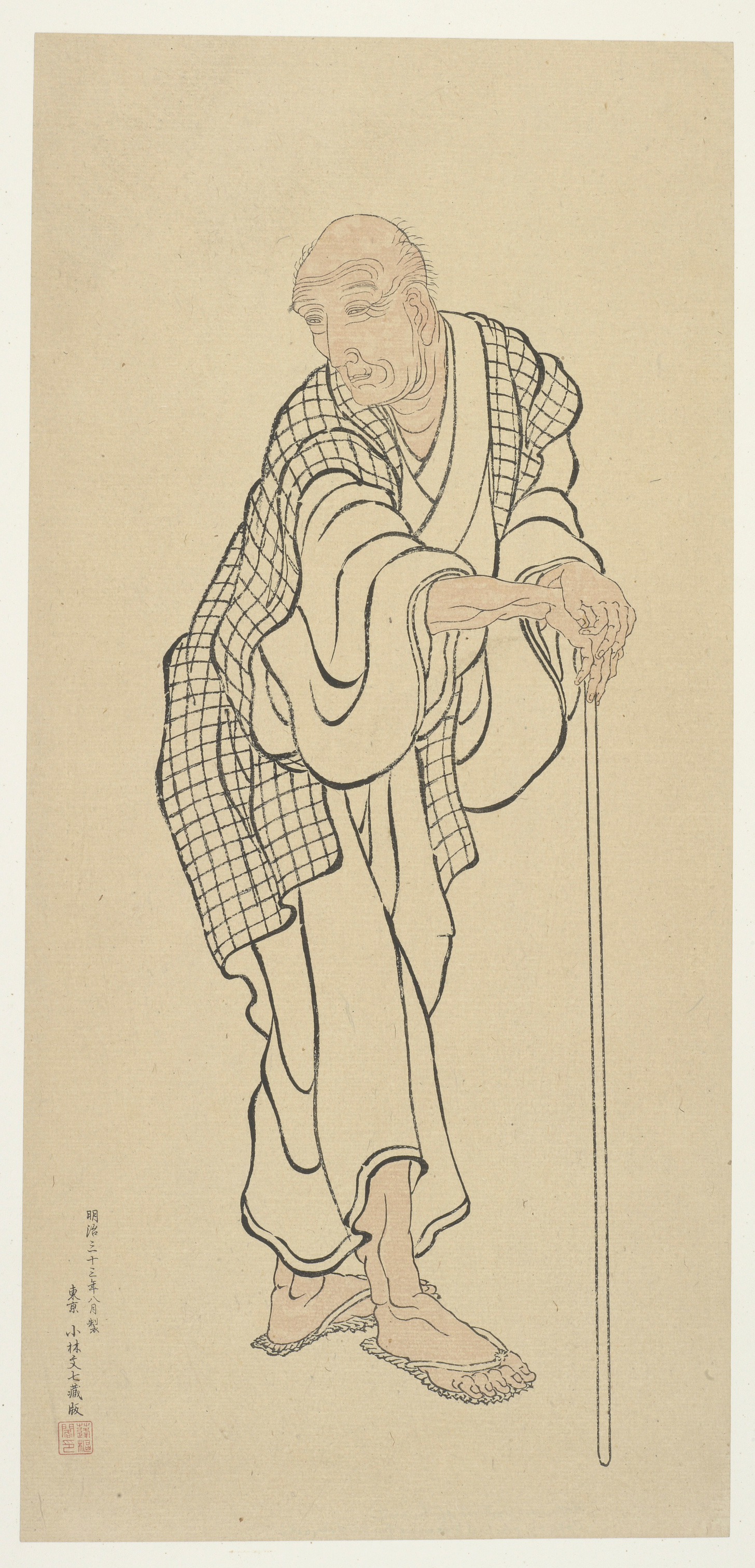

Hokusai; Self portrait as an old man. Date unknown. Public domain.

Hokusai Katsushika (1760 – 1849) lived a full, if not eccentric, life. The development of his artwork and continued influence moved diverse western artists like; Van Gogh and Monet. But his inspiration and very modern ways of working didn’t happen in a vacuum. It is said that very early on when he was beginning to cut his teeth as an artist he was exposed to French and Dutch copperplate engravings. I am certain that his experimentation with distance and perspective came out of the European tradition.

This is why the ‘Great Wave’ is so famous. Observe the way that mount Fuji viewed through the eye of the wave is diminished and shrunken under the massive movement of the water that appears to engulf it; the panicking boatmen there as a device for further scale references. The subtext is about the comparison of these various entities in size and distance. The earthbound Fuji is humbled by the might of a dramatic moving body of water; the ocean gets its revenge; Nature shakes her skirts.

Claws of the tiger.

Note in ‘Great Wave’ the repeated major and minor spirals; the smaller ones as kinds of ‘claws’ in the water.

‘Tiger in the Snow’, 1849. Private collection. Image: Public Domain.

The claw motif features in another of my favourite Hokusai images, ‘Tiger in the Snow’, seen as a lesser work, but for me it has amazing strengths; not just because Hokusai seems to have an affinity and appreciation for feline grace (see his drawings of cats) but how he bends reality and goes beyond a mere naturalistic representation.

The tiger’s claws are visible despite the snow, and the claw pattern is repeated in the foliage. Hokusai seems to have his own take on how tiger’s stripes should go; these are more swirls of blended colour, which enhance the muscularity of the big cat. And also, is it a snarl, or a smile on the face of the tiger?

It is reputed to be the very last image Hokusai produced; not a print, like the Great Wave, but a painting in ink on silk. Hokusai’s inscription on the painting reads, "Month of the Tiger, Year of the Cock, old Manji, the old man mad about painting, at the age of ninety". Art historian Narazaki Muneshige said of the artist and the painting, “While the artist's body was emaciated and bones wearied by age, in his thoughts he was a charging tiger".

Other eccentricities.

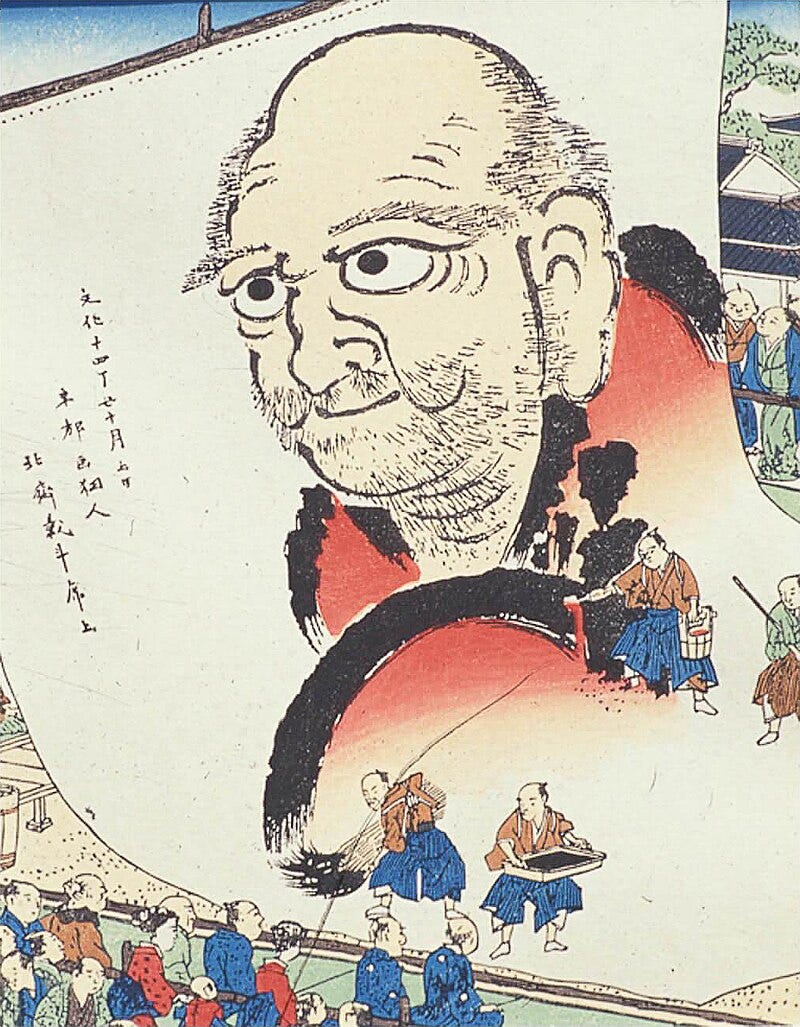

One of Hokusai most dramatic pieces of artwork was a huge banner 200 square metres in size. Painted in 1804, its subject, ‘The Great Daruma’ (Bodhidharma). He is said to have used buckets of paint and brooms to execute it. Hokusai had a dramatic flair for self-promotion.

A contemporary print from 1817 showing Hokusai painting the banner.

Another image of Hokusai brushing his huge painting.

Credit: By Kōriki Enkōan - https://peterromaskiewicz.com/2019/08/02/drawing-the-face-of-bodhidharma-a-brief-survey-of-an-artistic-tradition/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=95729738

The actual banner survived until 1945, when it was destroyed by the American bombing of the city of Nagoya during the Pacific War.

But my favourite story about Hokusai is a stunt he pulled in front of the then Tokugawa Shogun.

He’d been invited to the court in a kind of paint-off with another more traditional well-known artist. Not really wanting to play the game, Hokusai painted a speedily rendered blue curve and then somehow produced a live chicken, which he put wet red paint on its feet and encouraged it to run across his artwork. The end result, Hokusai claimed, was a picture of the Tatsuta River with red maple leaves floating across it. Naturally it was a major success.

I am going to try this myself, but bypass the live chicken and instead use chicken feet from my local butcher.

Hokusai’s talented and rebellious daughter.

Hokusai’s gifted daughter by his second marriage is known by the name of Katsushika Ōi. Very unlike his other daughters, she refused to go down the traditional route. Although briefly married to another artist, it didn’t last long, as she was far more skilled than he was, and let him know it.

Image of Hokusai’s daughter, with a traditional Japanese tobacco pipe.

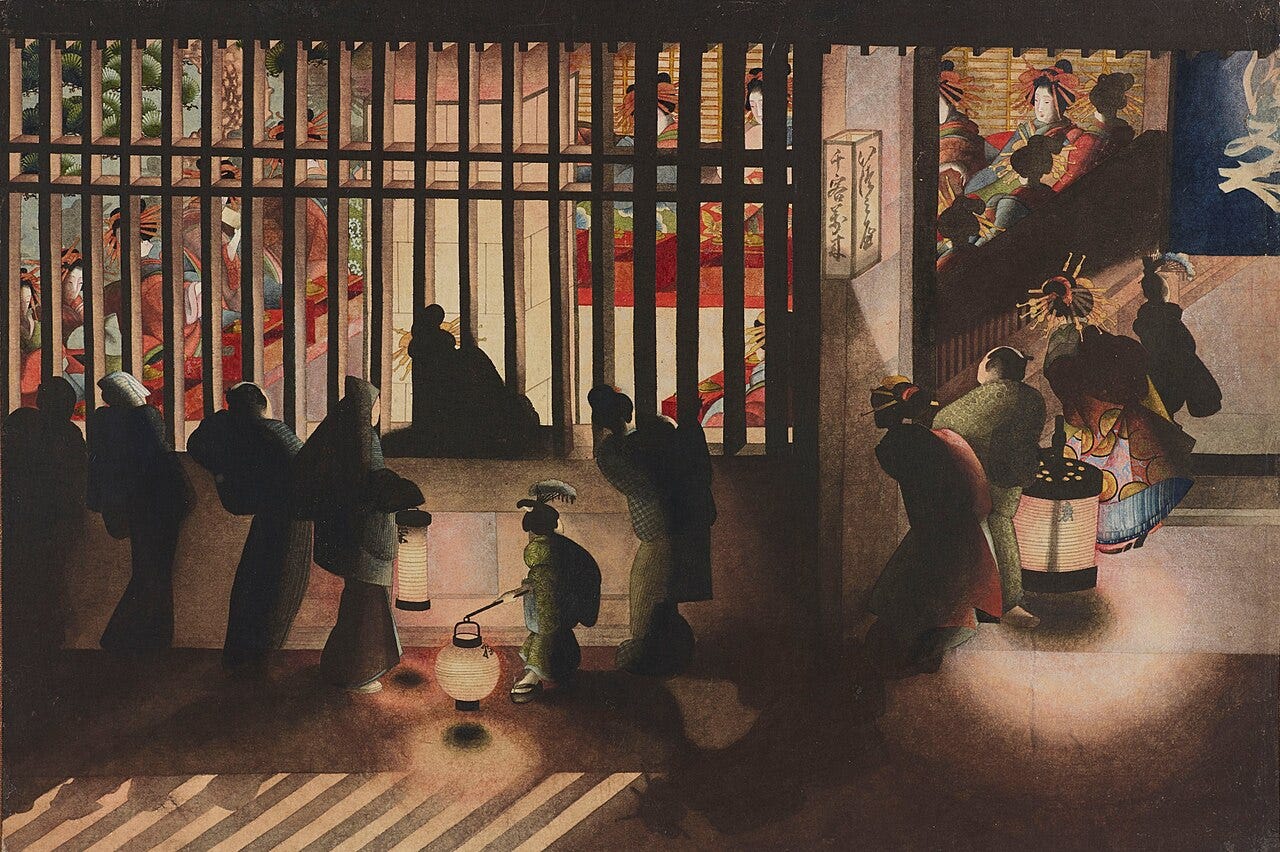

She returned to her father’s home and workshop and continued to live and study alongside him for many decades, just the two of them, she never married again. They were reputed to exist in a state chaos, focussed only on the production of artwork. She learned much from her father, but clearly was developing her own style.

Enjoy this image; ‘Night scene in the Yoshiwara’ 1860.

Credit: Katsushika Ōi, Japanese Ukiyo-e artist of the 19th century - Ōta Memorial Museum, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44443912

Personally, I find her work a step on from her father’s approach. She became her own person and much has been made of her legacy, including, in recent times, novels written about her life, as well as film dramas. Katsushika Ōi has become something of a feminist icon, in a world seemingly dominated by men.

Movie poster; TV Movie 2017, source IMDB.

Conclusion.

For me Hokusai is more than just ‘The Wave’. I suspect westerners take an outdated view of artistry that flourished outside of their own tradition, viewing it as quaint or rustic, somehow lacking the roots of classicism that westerners claim as their own.

Hokusai was a visionary; his daughter nudged the dial a few notches further. Her tradition seemed to end with her and new kids on the block like Hiroshige swerved into another direction.

Check out Hokusai’s ‘Manga’ (drawings), sample ‘how-to-do-it’ drawing books; beautiful simplified line drawings in ink. These were very popular in the 19th century.

Great write up! Hokusai and his Great Wave is a personal favorite of mine too.

there's a quote attributed to Hokusai that represents this lifelong pursuit of mastery I'd like to embody:

"Ever since I was six I’ve been obsessed by drawing the form of things. By the time I was fifty I had published an endless number of drawings, but everything I produced before the age of seventy is not worth counting. Not until I was seventy-three did I begin to understand the structure of real nature, animals, plants, trees, birds, fish, and insects.

Consequently, by the time I am eighty-six, I will have made even more progress; at ninety I will have probed the mystery of things; at a hundred I will undoubtedly have attained a marvelous pinnacle, and when I’m a hundred and ten, everything I do, be it a dot or a line, will be alive.

I would ask anyone living as long as I to see if my word holds true."