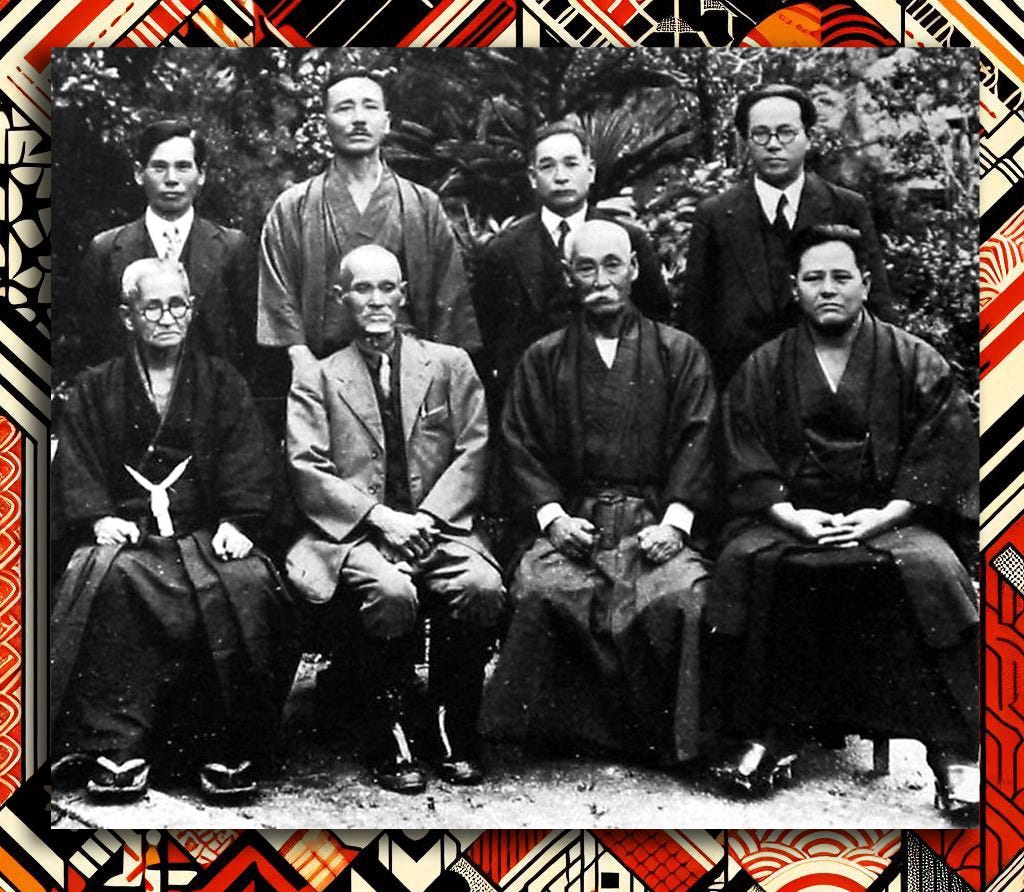

Header image: Okinawan karate masters in 1936. Front row L to R; Kyan, Yabu, Hanashiro, Miyagi. Back row L to R: Shiroma, Maeshiro, Chibana, Nakasone.

In this second piece:

· Giving Okinawan karate some moral substance.

· Just what were the Japanese looking for in Okinawan karate?

· The urge to compete.

· Downplaying anything that looked like throwing techniques – why?

· Three ways of looking at Okinawan karate compared to Japanese karate – according to master Otsuka.

· Karate as a mass participation event? Or, bespoke, individualised training?

If you missed out on the second half of Part 1, where I discussed the nature and origins of Okinawan karate; become a paid subscriber to access all premium posts, which is becoming a growing library of in-depth material.

Common ground.

Looking for the aspects of commonality between Okinawan karate as an art of the islands and Japanese Bujutsu/Budo, the first thing I would reach for was the moral and philosophical base. I will take Funakoshi Gichin as my prime example.

Master Funakoshi (1868 – 1957) was the first significant bridge builder between Okinawan karate and Japanese Gendai Budo. Funakoshi was an educated man and had studied the Chinese and Japanese classics and was able to relate these to the morality of karate, as he saw it. This did two significant things; firstly, it helped to elevate Okinawan karate and save it from itself as possibly appearing an art for ruffians. Secondly, the Confucian outlook chimed with the Japanese martial arts establishment; basically, Funakoshi could speak their language.

Tokyo 1930. 2nd from left Otsuka. 4th from left Funakoshi, 5th Motobu, 6th Mabuni.

Bones of contention.

Three significant questions came out of the identity of Okinawan karate as it arrived on the mainland:

1. Was it an efficient and usable fighting system, one that was on a par with the emergence of judo out of the older Koryu unarmed methods?

2. Was its utility worth investing in, for the good of the nation and Japanese youth?

3. Could it be moulded to fit with the emerging urge for contest and sport?

On that last question; it is interesting that Funakoshi was really resistant to any form of competition in karate; which, in his head, he fell back on point number 1 and treated it as his ace card by stating that the effectiveness of karate made it far too dangerous to use for duelling or contest.

But, this was going to be a losing battle for him and any other Okinawan ultra-conservative karateka, as the urge to ‘test’ the credibility of karate became too tempting for some of Funakoshi’s senior students, among those one Otsuka Hironori. The paired drills that Otsuka (and others) developed, was only one tiny step away from free-form sparring.

A quote/translation on the development of contest sparring, from some of Otsuka Hironori’s later writings:

“Around 1929, at the suggestion of a member of the University of Tokyo, protective gear was constructed and an attempt was made to hold matches in which this protective gear was worn. At the time, I was the instructor of the University of Tokyo Karate Research Society, so we conducted research using bare hands, and have continued to do so to this day. This was the beginning of the modern-day matches. Research into the sport also began among ordinary students around 1941-1942, progressing to the student federation matches we see today”.

Wado master Suzuki Tatsuo was of a time to witness how this developed, when ‘exchange demonstrations’ quickly flipped into matches, and then turned into rough-housing.

How to fit in among all the older kids in the schoolyard.

According to Japanese Shotokan teacher Kousaku Yokota, Okinawan karate did well to ‘stay in its lane’. In his recent writings he suggests that in those early days anything that looked like throwing techniques in Okinawan karate trespassed too much into the zone of the judo/jujutsu guys. Add to that, as specialists, the judoka were highly skilled in subtleties that existed in Okinawan karate seemingly only at the level of grappling; including a fair measure of ‘seize, pull and hit’.

(As an aside; I always wanted to believe that Okinawan karate inherited from China some form of grappling/manipulation that can be found in a method sometimes called, ‘Chin Na’ or ‘Qin Na’, which means ‘seize and hold’. Although not an independent system, it was included as part of certain schools of Chinese Chuan Fa. But, In my limited experience, I cannot see any evidence of that level of sophistication in Okinawan karate, but maybe I am missing something?).

Mural in the Shaolin Temple.

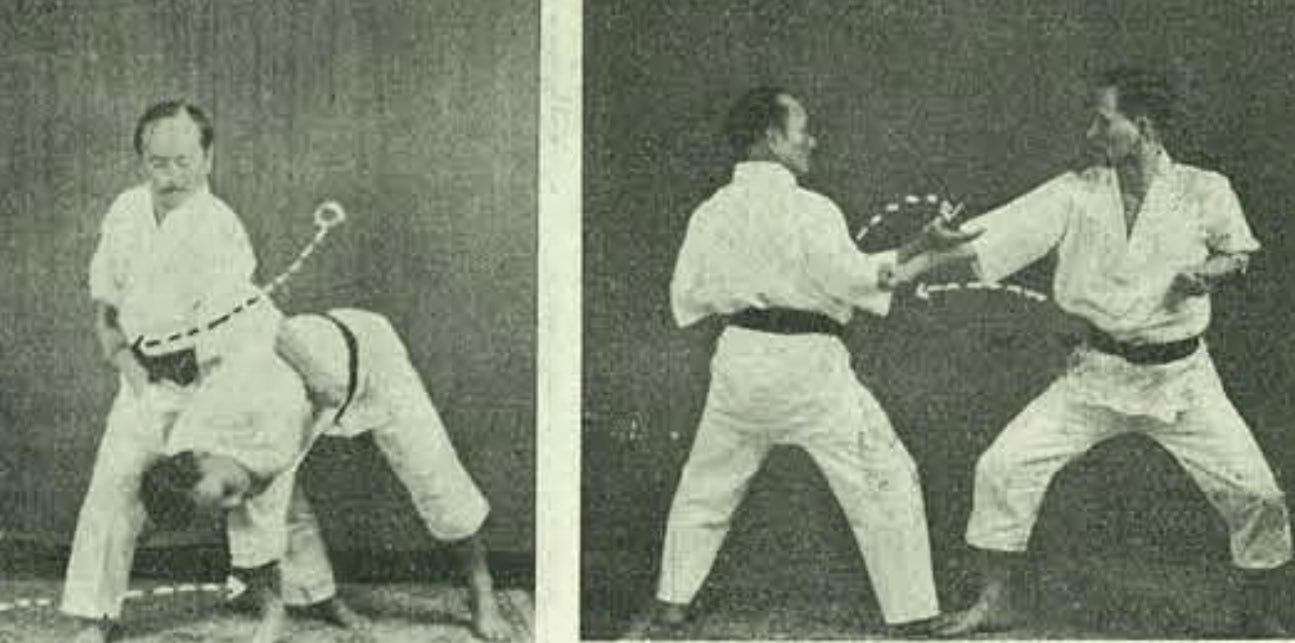

If you look at what Funakoshi presented as throwing and grappling techniques shown for self-defence, they look very rudimentary (even with Otsuka as a jujutsu man helping out). Many of the so-called ‘Bunkai’ that appeared very late in the game, struggle to resemble anything that the jujutsuka were able to do.

Interestingly, later on, Otsuka Sensei within Wado Ryu, felt obliged to create a set of techniques for women’s self-defence. By their nature they had to be simplified, and mechanically they are very very basic – unless in the hands of Otsuka himself, where I believe, because of his training, the unseen subtleties would kick in at an unconscious level. But, I am fairly sure that there’s hardly anyone out there who is capable of replicating exactly what Otsuka was able to do, even though he might have been unable to explain it himself.

Funakoshi performing techniques on Otsuka.

Featuring in the rest of this piece; Motobu and Otsuka talk jujutsu. Funakoshi humiliated in his rivalry with Motobu. Otsuka defines what HE thinks is the differences between Okinawan karate and Japanese karate.